A Lonesome Heart Drifting Through Time and Distance

When “Speed of the Sound of Loneliness” was written and first recorded by John Prine in 1986 for his album German Afternoons, it did not storm the pop charts. It was never designed to. Instead, it quietly settled into the hearts of listeners, eventually reaching No. 6 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart when covered by Nanci Griffith in 1993 as a duet with Prine himself. Over time, the song became one of Prine’s most beloved compositions—an aching meditation on emotional distance within love, and the strange quiet that follows intimacy’s fading warmth.

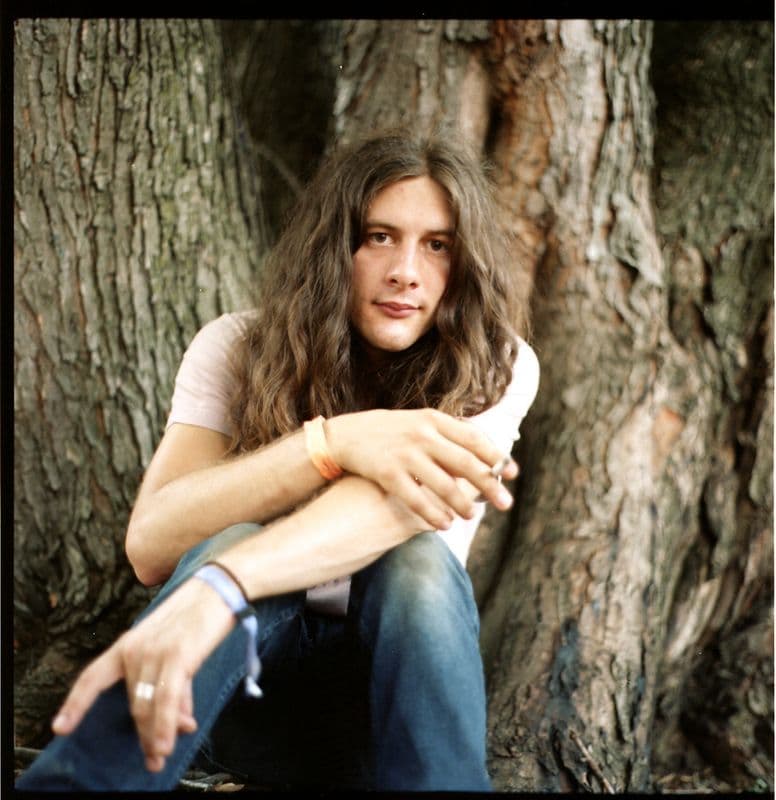

Decades later, in 2018, Kurt Vile offered his own interpretation on the tribute album Come On Up to the House: Women Sing Waits—though more significantly, he performed it live and included it in sessions that reflected his deep reverence for Prine. Vile’s version does not attempt to outshine the original; instead, it drifts alongside it, like a younger traveler tracing the footsteps of an elder songwriter.

The original “Speed of the Sound of Loneliness” is built on a deceptively simple question:

“You come home late and you come home early / You come on big when you’re feeling small…”

From the opening lines, Prine paints a portrait of two people orbiting one another but never quite touching. It is not a song about explosive heartbreak; it is about something quieter—and perhaps more devastating. The gradual erosion of connection. The sense that love hasn’t ended, but has slowed to a distant echo.

When Nanci Griffith revived the song in 1993 on her album Other Voices, Other Rooms, it became a country hit, reaching No. 6 on the Billboard country chart. The duet format gave the song a new dimension: instead of a solitary voice pondering loneliness, it became a conversation—two perspectives suspended in midair, unable to close the gap between them. That chart success introduced the song to a broader audience and cemented its place in the modern American songbook.

But what makes this song endure is not its chart position. It is the craftsmanship. John Prine had a rare gift for expressing complicated emotions in plainspoken language. There is no grand metaphor here—no storm, no fire, no dramatic farewell. Just the slow recognition that something has shifted. The title itself is one of the most quietly brilliant phrases in songwriting history. “The speed of the sound of loneliness” suggests that loneliness travels fast, but it also suggests that it travels silently. By the time you hear it, it has already arrived.

Enter Kurt Vile—a songwriter of a later generation, known for his hazy, reflective indie-folk style. His interpretation of “Speed of the Sound of Loneliness” feels almost like a letter of gratitude to Prine. Vile slows the tempo slightly, allowing the spaces between lines to breathe. His voice carries a detached tenderness, less wounded than weary. Where Prine sounds puzzled and vulnerable, Vile sounds contemplative—as though he has lived with the song long enough to accept its truths.

In Vile’s hands, the song becomes less about a specific relationship and more about the universal human condition: how we drift, how we misread one another, how love can coexist with isolation. The arrangement leans into gentle guitars and a relaxed cadence, echoing Vile’s signature lo-fi sensibility. Yet the core remains untouched—the melody, the structure, the unadorned honesty.

The story behind the song’s creation adds another layer. Prine once described writing it during a period when he was observing relationships unravel around him. He understood that loneliness is not always the absence of someone—it is sometimes the presence of someone who no longer truly sees you. That insight, delivered without bitterness, is what gives the song its lasting power.

Listening today, one cannot help but feel a wave of memory rising. For those who have loved deeply, lost quietly, or simply watched time carry relationships into different shapes, “Speed of the Sound of Loneliness” resonates with unsettling clarity. It does not accuse. It does not blame. It simply asks.

And in that question—“What in the world has come over you?”—we hear not anger, but longing.

Kurt Vile’s rendition reminds us that great songs are not bound by era. They travel across decades, carried by new voices, gathering new shades of meaning. The song that began on German Afternoons in 1986 continues to echo—softly, steadily—through generations.

In the end, the speed of loneliness may be swift. But so too is the endurance of a beautifully written song.