They Ruled the Airwaves—So Why Did History Leave Three Dog Night Behind?

From 1969 to 1974, no American band moved more records or filled more seats than Three Dog Night. That’s not an opinion—it’s math. Twenty-one Top 40 hits. Three No.1 singles. The biggest-selling song of 1971. When I started putting this video together, that contradiction became the engine of the story: how does a band this successful end up feeling like a footnote?

I chose to tell this story geographically, because Three Dog Night is inseparable from Los Angeles. It starts in Burbank, with Danny Hutton unloading record boxes at Disney Studios, already obsessed with what music could become. He spotted The Beatles before most of L.A. knew their name, and that instinct—seeing the future early—would define everything that followed. Danny wasn’t chasing teen-idol fame; he was chasing something bigger, something lasting.

Then there’s Cory Wells, arriving from Buffalo and cutting his teeth at the Whisky a Go Go. His voice had weight, soul, and authority—the kind that stopped people mid-conversation. Chuck Negron brought something else entirely: vulnerability. When the three of them finally sang together, it wasn’t clever branding—it was chemistry. Three lead singers in one band wasn’t supposed to work. Somehow, it did.

Brian Wilson understood that immediately. The near-miss with the Beach Boys’ Brother Records—when the band was briefly called Redwood—is one of those “sliding doors” moments I wanted to linger on in the video. If that deal had gone through, rock history might look very different. But instead of rewriting the rules, Three Dog Night found themselves becoming the perfect AM singles band.

That distinction matters. They weren’t a band critics loved to mythologize. They were interpreters—masters at finding overlooked songs and turning them into undeniable hits. “One.” “Mama Told Me Not to Come.” “Black and White.” “Joy to the World.” These weren’t just successful records; they were cultural events. Songwriters like Randy Newman built careers on the back of Three Dog Night’s instincts.

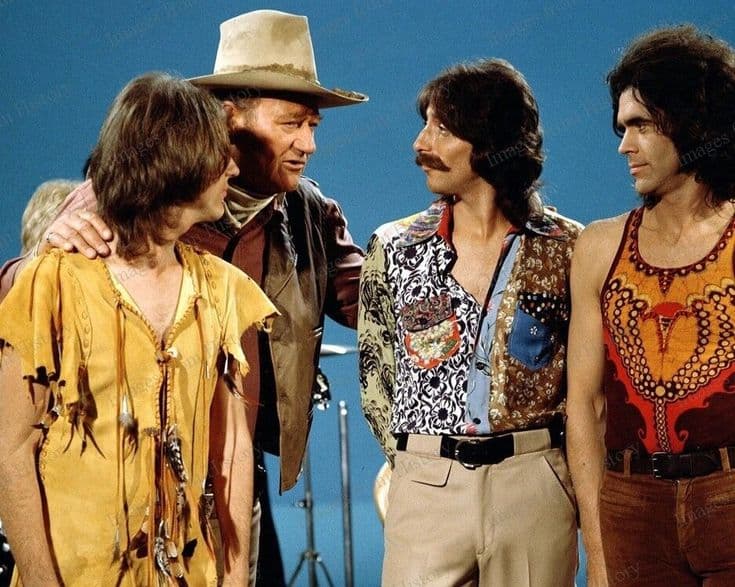

But the machine that elevated them also consumed them. As I show in the later part of the video, success became relentless. Endless touring. Corny promotional stunts. A management system squeezing every last dollar out of a band that was too exhausted—or too altered—to fight back. Party culture wasn’t a side note; it was structural. Laurel Canyon wasn’t just a neighborhood, it was a lifestyle with consequences.

The hardest section to put together was Chuck Negron’s descent. By the early ’80s, the voice behind some of the most joyful songs of the era was trapped in addiction, surrounded by tragedy. That contrast—between the brightness of the music and the darkness of the aftermath—is the emotional core of this story.

By the time the original band fractured, the damage was done. Three Dog Night had sold more records and played to more people than almost anyone of their generation—yet they remain outside the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. That omission isn’t just ironic; it’s revealing. Their crime may have been being too popular, too efficient, too good at making hits.

This video isn’t an elegy. It’s a correction. Three Dog Night weren’t just successful—they defined what American pop-rock sounded like at its peak. History didn’t forget them because they didn’t matter. History forgot them because they made it look easy.