A Tender Lament for a Vanishing Home and a Fading Way of Life

Few songs in the American folk canon capture loss, memory, and quiet indignation as poignantly as “Paradise” – John Denver. Released in 1972 on the album Rocky Mountain High, Denver’s version brought wider national attention to a song originally written by John Prine in 1971. While Denver’s recording was not issued as a major charting single in the United States—therefore not reaching the upper tiers of the Billboard Hot 100—its enduring radio presence and its association with Denver’s platinum-selling album secured its place in the cultural memory of the 1970s folk revival.

At its core, “Paradise” is a song about a small coal-mining town in Muhlenberg County, Kentucky—Paradise, in fact—that was largely destroyed by strip mining operations conducted by the Peabody Coal Company. When John Denver chose to record it, he was already becoming one of the defining voices of gentle, reflective American songwriting. Following the massive success of “Take Me Home, Country Roads” (which reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1971) and the title track “Rocky Mountain High” (which peaked at No. 9 in 1973), Denver was building a repertoire that blended personal nostalgia with broader environmental consciousness. “Paradise” fit seamlessly into that narrative.

The story behind the song, however, begins with John Prine, who wrote it as a deeply personal reflection on his father’s hometown. Prine never lived in Paradise himself, but he grew up hearing stories about it—stories of green rivers, community life, and a slower rhythm that belonged to another era. When strip mining erased much of the town, it symbolized something far larger than industrial change; it became emblematic of how progress often tramples memory. Denver’s interpretation honors that spirit. His clear tenor, unadorned and sincere, gives the song a communal warmth, as if he were not merely telling Prine’s story but singing on behalf of countless small towns altered by modern industry.

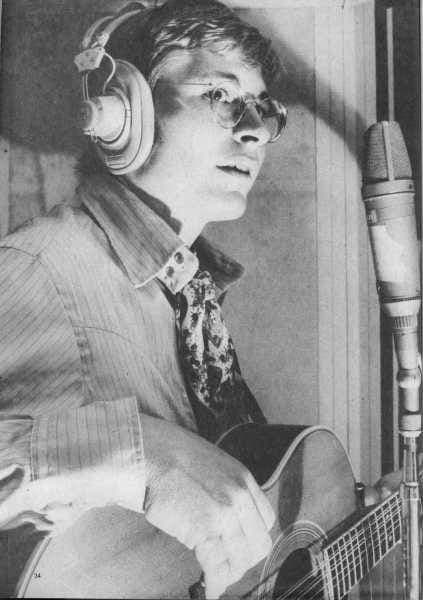

Musically, Denver’s version is deceptively simple. Gentle acoustic strumming anchors the melody, allowing the narrative to take center stage. There is no grand orchestration, no dramatic flourish—only a steady, almost hymn-like progression. That simplicity is crucial. It mirrors the modest lives the song describes and intensifies the emotional weight of lines like, “And daddy, won’t you take me back to Muhlenberg County.” When Denver sings those words, one hears not anger alone, but longing—an ache for continuity, for a place where roots once ran deep.

The song’s meaning extends beyond environmental protest. It is about inheritance—about what is passed down not just in land or property, but in stories. “Paradise” asks a painful question: what happens when the physical landscape that shaped our memories disappears? For many listeners in the early 1970s—an era marked by rapid industrial expansion and growing ecological awareness—the song resonated as both elegy and warning. It aligned naturally with Denver’s emerging identity as a gentle environmental advocate, years before sustainability became a common cultural conversation.

What makes “Paradise” endure is its refusal to become strident. It does not shout; it remembers. The chorus lingers like a conversation at a kitchen table long after supper, when recollections drift in and out with the evening air. Denver’s interpretation softens Prine’s sharper irony, leaning instead into tenderness. The result is not diminished power, but a broadened appeal—an invitation for listeners to reflect on their own “Paradise,” whatever shape it once took.

Over the decades, the song has been covered by numerous artists, yet the pairing of John Denver and John Prine remains especially meaningful. It represents a bridge between two traditions of American songwriting: Prine’s wry, working-class storytelling and Denver’s luminous pastoral romanticism. In Denver’s hands, “Paradise” became less a regional lament and more a universal meditation on loss.

Listening to it today, one cannot help but feel the quiet gravity of time. Places change. Rivers are rerouted. Communities scatter. Yet a song like “Paradise” preserves what bulldozers cannot touch—the emotional geography of memory. And perhaps that is why, more than five decades later, its gentle refrain still feels like an open door to a world we once knew, and still carry within us.