An Enduring Elegy of Betrayal and the Weight of Survival

There are songs, and then there are legends—ballads that feel as ancient and elemental as the dust of the trail they chronicle. “Pancho and Lefty,” often cited as Townes Van Zandt’s masterpiece, falls squarely into the latter category. It is a haunting, elliptical tale of two outlaws, a Mexican bandit, and his quiet friend, that poses far more questions than it answers, allowing the listener to step into the lonely landscape of its tragedy.

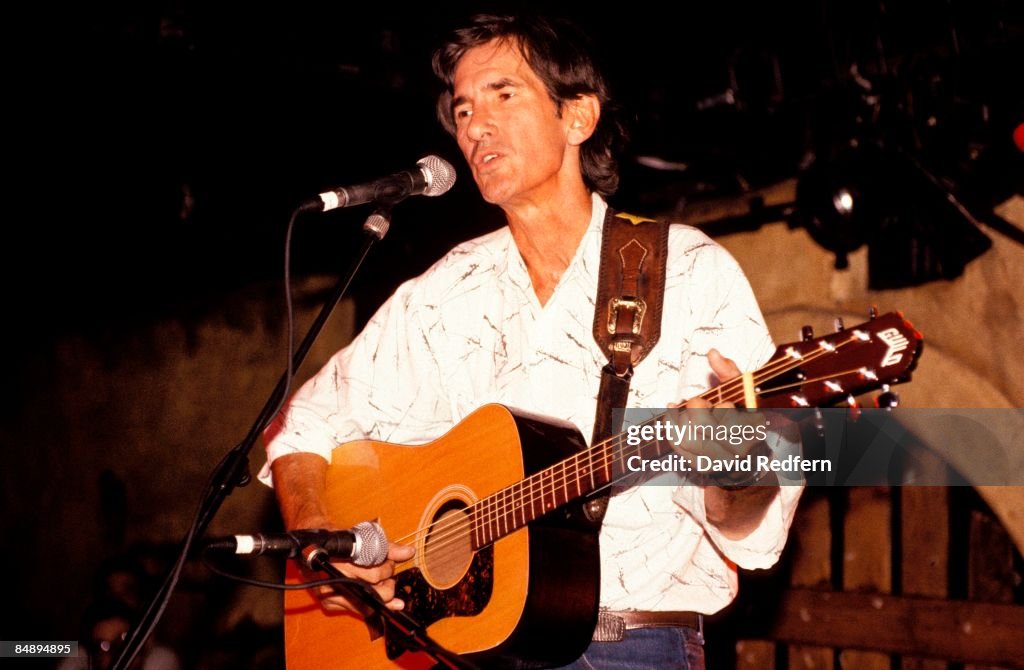

The song was originally released on Townes Van Zandt’s 1972 album, The Late Great Townes Van Zandt. For the songwriter himself, a troubled poet whose genius was frequently overshadowed by his personal struggles, the song, like much of his own work, went largely unnoticed at the time of its release. The original Townes Van Zandt version, a stark, acoustic rendering, did not chart and its parent album did not make any music charts.

However, the song’s destiny was not to remain a treasured secret of folk aficionados. Its true commercial breakthrough arrived more than a decade later when Country music titans Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard covered it. Their 1983 duet, released as the title track of their album Pancho & Lefty, was a colossal success, soaring to Number 1 on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart in the US and the RPM Country Tracks chart in Canada. This version, with its early ’80s production, provided Townes Van Zandt with much-needed royalties, though he reportedly remained indifferent to the commercial success of his own composition.

The story behind the song is almost as compelling and mysterious as the lyrics themselves. Van Zandt famously wrote the song in a cheap, solitary hotel room near Denton, Texas, after being displaced by a huge Billy Graham festival that had booked up all the “decent” lodging. He claimed the song “drifted through the window,” and upon being asked by Willie Nelson what it meant, he simply replied, “I don’t know.” He once suggested it might be about the two police officers, an Anglo and a Hispanic, who were called “Pancho and Lefty” and who stopped him and a friend one day. This ambiguity only heightens its power.

Lyrically, the song is a compact novel, telling the story of Pancho, the charismatic Mexican bandit, and his friend Lefty. Pancho meets a lonely, violent end “on the deserts down in Mexico,” and “The poets tell how Pancho fell / And Lefty’s living in cheap hotels.” The true meaning, however, is woven into the line implying Lefty’s betrayal: “The day they laid poor Pancho low, / Lefty split for Ohio. / Where he got the bread to go, / There ain’t nobody knows.” The song contrasts Pancho, who dies an honorable outlaw’s death, with Lefty, who trades his friend’s life for money and lives out his days in quiet, cold regret. It’s an elegy on the high cost of survival, the shame of betrayal, and the relentless march of time. Townes Van Zandt asks for prayers for both, recognizing Pancho’s tragic life but also Lefty’s grim, enduring fate: “He only did what he had to do / And now he’s growing old.” For older listeners, the song’s themes of youth’s lost dreams and the compromises of adulthood resonate deeply, evoking a profound sense of nostalgia for paths chosen and paths forever closed.