A restless prayer for dignity and escape, sung across generations with quiet grace

When John Mayer performs “Angel from Montgomery,” he is not claiming the song as his own so much as stepping gently into a long, living tradition. The song was written by John Prine and first released in 1971 on Prine’s self-titled debut album, John Prine—an album now widely regarded as one of the great American folk records of the 20th century. At the time of its release, “Angel from Montgomery” was not issued as a commercial single and therefore did not enter the Billboard charts. Yet its absence from the charts has never reflected its true stature. Over the decades, the song has grown into a modern folk standard, passed from voice to voice like a shared confession.

The narrator is a middle-aged woman, weary and emotionally stranded, speaking from the quiet confines of a small life that once held promise. This perspective alone marked Prine as a rare songwriter. In an era dominated by youthful bravado and masculine certainty, he chose empathy over ego. The song’s opening line—“I am an old woman, named after my mother”—lands not as a literary trick, but as an act of moral imagination. Prine was in his early twenties when he wrote it, yet the voice feels lived-in, heavy with years, disappointment, and unspoken resilience.

The song gained its first wide audience through Bonnie Raitt, who recorded it in 1974 on her album Streetlights. Her version, earthy and restrained, became definitive for many listeners and helped embed the song into the American roots canon. Still, even Raitt’s recording was never a major chart hit. Its power spread more slowly—through FM radio, live performances, and the deep listening habits of people who valued songs that spoke softly but truthfully.

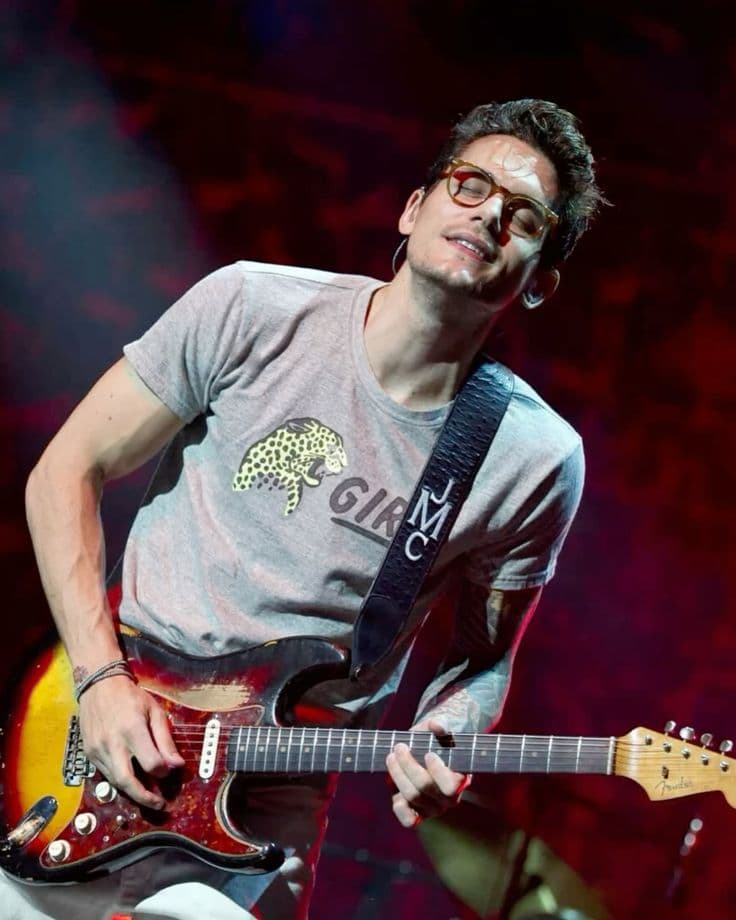

Enter John Mayer, an artist often associated with polished pop success and virtuoso guitar work. His relationship with “Angel from Montgomery” surprised many listeners, and perhaps revealed more about Mayer than any of his radio hits. His most famous performance came during Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festival in 2004, where Mayer shared the stage with John Prine himself. That performance—later widely circulated—became a turning point in how Mayer was perceived. Standing beside the song’s creator, Mayer did not dominate or modernize the piece. Instead, he listened. His guitar phrasing was spare, respectful, almost deferential, allowing the song’s emotional architecture to remain intact.

Mayer’s voice, lighter and more fragile than Raitt’s, brings a different shade of longing. Where Raitt sounds grounded in hard-earned endurance, Mayer sounds like someone reaching across time, aware of the weight he is carrying. His interpretation does not change the song’s meaning, but it refracts it. The longing becomes more exposed, the pauses more telling. Silence, in his hands, becomes part of the lyric.

The meaning of “Angel from Montgomery” lies not in escape, but in the ache for it. The “angel” is not a miracle worker, but a symbol of remembered possibility—a version of the self that once believed life might open outward instead of closing in. Lines about rodeos, TV dinners, and faded dreams are not nostalgic decorations; they are the furniture of a life quietly endured. The song does not ask for pity. It asks to be seen.

What makes Mayer’s connection to the song so enduring is his understanding that greatness sometimes lies in restraint. He does not overwrite Prine’s wisdom with technical flourish. Instead, he treats the song as something borrowed and beloved. In doing so, he helped introduce John Prine’s songwriting to a new generation of listeners, many of whom traced the song backward, discovering the depth of Prine’s catalog for the first time.

Today, “Angel from Montgomery” exists outside of charts and eras. It belongs to listening rooms, late-night radio, and the private moments when a song feels less like entertainment and more like company. Through John Mayer’s performances, the song continues its long journey—unchanged in essence, yet endlessly renewed—reminding us that some of the most important music was never meant to be loud, young, or triumphant. It was meant to be honest, and to last.