A weary confession about temptation, friendship, and the quiet costs of living too fast

When people speak of Jackson Browne and Warren Zevon, they often picture two parallel paths in American songwriting: one introspective and elegiac, the other sharp-tongued and darkly ironic. Yet those paths crossed early, and one of the most revealing intersections is the song “Cocaine.” It is not a hit remembered for stadium sing-alongs, but a document of a moment, and of a friendship, that tells us much about both men and about the era they were trying to survive.

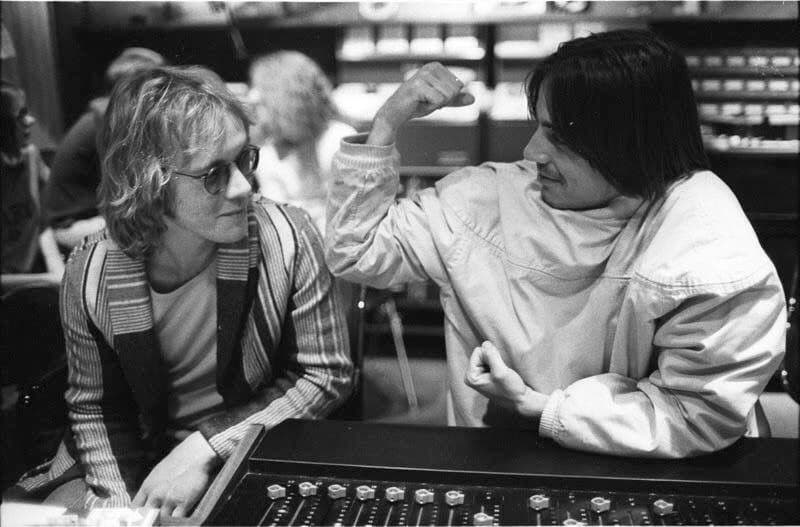

“Cocaine” was written in the early 1970s, a period when Browne and Zevon were closely connected in Los Angeles. Browne was already emerging as a major new voice of the singer-songwriter movement, while Zevon—brilliant, volatile, and still largely unknown—was struggling to find his footing. Browne helped him professionally and personally, producing Zevon’s early recordings and, at times, quite literally helping him stay afloat. The song “Cocaine” grew out of that shared environment: late nights, creative pressure, and the omnipresent allure of substances that promised clarity, stamina, or escape.

Released as a single by Jackson Browne in 1971, “Cocaine” made a modest but noticeable impact, reaching the lower end of the Billboard Hot 100 (around No. 30). It was not tied to a major album and has often been overshadowed by Browne’s later, more polished classics, yet its chart appearance mattered. It marked Browne as a songwriter unafraid to confront uncomfortable realities, even at a time when many radio hits preferred romance or abstraction.

Lyrically, “Cocaine” is striking for what it does not do. It does not glamorize excess, nor does it sermonize. Instead, it unfolds as a quiet confession, almost conversational in tone. The narrator speaks from inside the experience, aware of the pull and the temporary sense of control, but equally aware of the hollowness underneath. The song’s restraint is its power. There are no dramatic crescendos, only the steady realization that something promised relief but delivered dependency.

Musically, the arrangement is spare, rooted in the folk-rock sensibility that defined Browne’s early work. The melody drifts rather than drives, mirroring the emotional drift of the narrator himself. This understatement allows the words to linger. You can hear the fatigue in the phrasing, the sense of someone who has already stayed too late at the party and knows it.

The presence of Warren Zevon in the song’s story is crucial, even if his name is not sung aloud. Zevon would later confront addiction head-on in songs like “Carmelita,” and with a sharper, more sardonic edge. In “Cocaine,” by contrast, the perspective is gentler, more hesitant. It feels like an early warning, offered quietly between friends, before the consequences fully arrived. In retrospect, knowing Zevon’s later struggles and eventual clarity, the song takes on added weight. It becomes not just a snapshot of a scene, but a prelude.

For listeners who lived through that era—or who remember its music as the soundtrack of youth—“Cocaine” carries a particular resonance. It belongs to a time when freedom and self-expression were celebrated, yet the costs were not always acknowledged out loud. Browne’s gift was his ability to acknowledge them without bitterness. He sang as someone still searching, still hoping that awareness itself might be a form of salvation.

Today, “Cocaine” stands as a lesser-known but deeply revealing piece in Jackson Browne’s catalog, and an early marker of his bond with Warren Zevon. It reminds us that some songs are not meant to dominate the charts or define an artist’s legacy. Their purpose is quieter: to tell the truth as gently as possible, and to leave space for the listener’s own memories to rise. In that sense, the song endures—not as a relic of excess, but as a thoughtful, human reckoning with temptation and time.