When a Voice Doesn’t Seek to Comfort, but Forces Us to Face Our Own Pain

There are artists who do not enter our lives with a blaze of glory, but with a faint scratch—one that lingers for a very long time. For me, Townes Van Zandt is one of them. His music is not loud, does not try to soothe or reassure; instead, it quietly opens up the hidden corners of the soul, the places we usually avoid. Listening to Townes, I often feel as though someone is finally speaking the words I never dared to name.

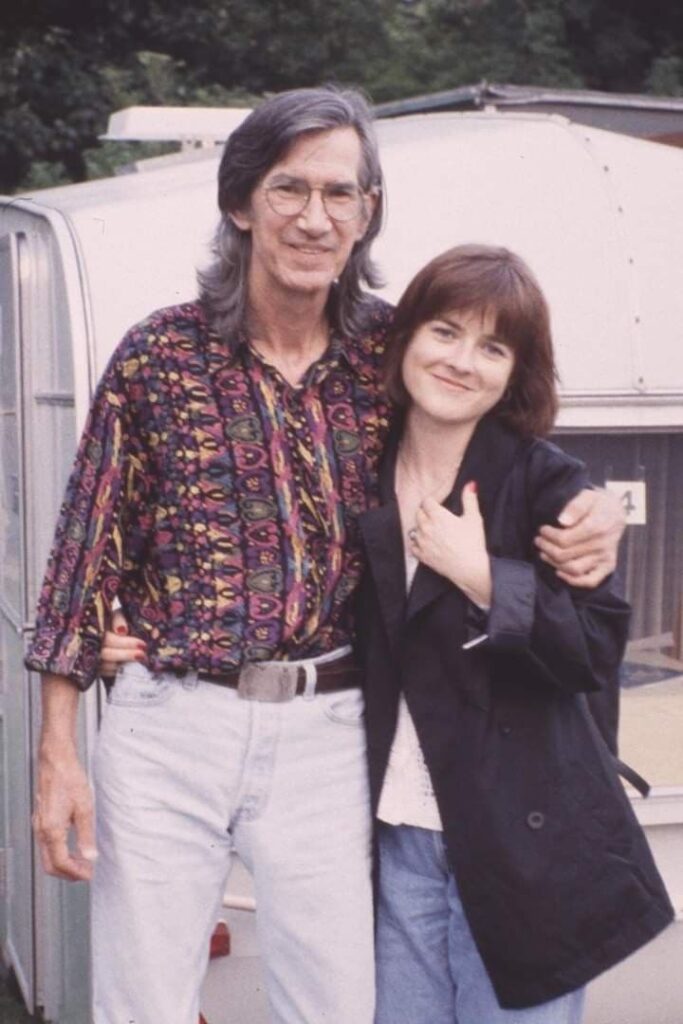

Townes was never one to chase fame. He seemed concerned only with listening to himself, digging deep into sadness, loneliness, and the emotional wounds that followed him from an early age. At a time when country music was becoming increasingly polished, radio-friendly, and easy to consume, Townes chose a narrower path: stripped-down melodies, heavy lyrics, and haunting silences. It is within those silences that I sense his spirit most clearly—fragile, honest, and utterly unguarded.

Townes’s life story fills me with both respect and sorrow. He did not grow up in poverty, yet he struggled with depression from a very young age. Brutal treatments, erased memories, and then alcohol and drugs—uninvited companions—quietly gnawed at him for years. The most painful realization is this: the very source of his suffering nourished his music, while at the same time pushing him closer and closer to the edge.

When I hear Townes sing, I don’t feel as if I’m listening to a “performance.” It feels more like a confession. Each song is a slice of life in which sadness is neither dressed up nor apologized for. Songs like “Pancho and Lefty,” “If I Needed You,” or “Tecumseh Valley” are not merely stories about fictional characters; they are reflections of Townes himself—a man perpetually suspended between fragility and resilience. Although many others turned these songs into commercial successes, to me, Townes’s own versions remain the most painful, because they carry the weary breath of an entire lifetime.

Townes’s final years were deeply unsteady. He survived on small gigs, the kindness of friends, and meager royalty checks. His body weakened, his spirit worn down, yet he continued to step onto the stage, to hold his guitar, to sing. Perhaps because, for him, singing was not a choice but a final instinct for survival. What I see there is not the romanticized image of a tortured artist, but the frail yet persistent effort of a man who never learned how to abandon himself.

When Townes passed away at the age of fifty-two, the world did not stop. But for those who truly listened to him, a very real emptiness remained. What convinces me that he is still alive, in a way, is that his music has never grown old. It continues to speak truthfully about loneliness, about failures with no clear resolution, about the low-burning sorrow many people carry after crossing the midpoint of their lives.

Townes Van Zandt reminds me that not every story has a redemptive ending. Sometimes, the most beautiful thing a person can do is to be utterly honest with their pain—and turn it into song. And perhaps that alone is already a legacy large enough.