A Gentle Reflection on Loneliness: David Allan Coe – Hello in There

When David Allan Coe released his album Hello in There in September 1983, the title carried a weight far deeper than a simple country ballad—it was a whisper into the vast, quiet spaces of aging and forgotten lives.

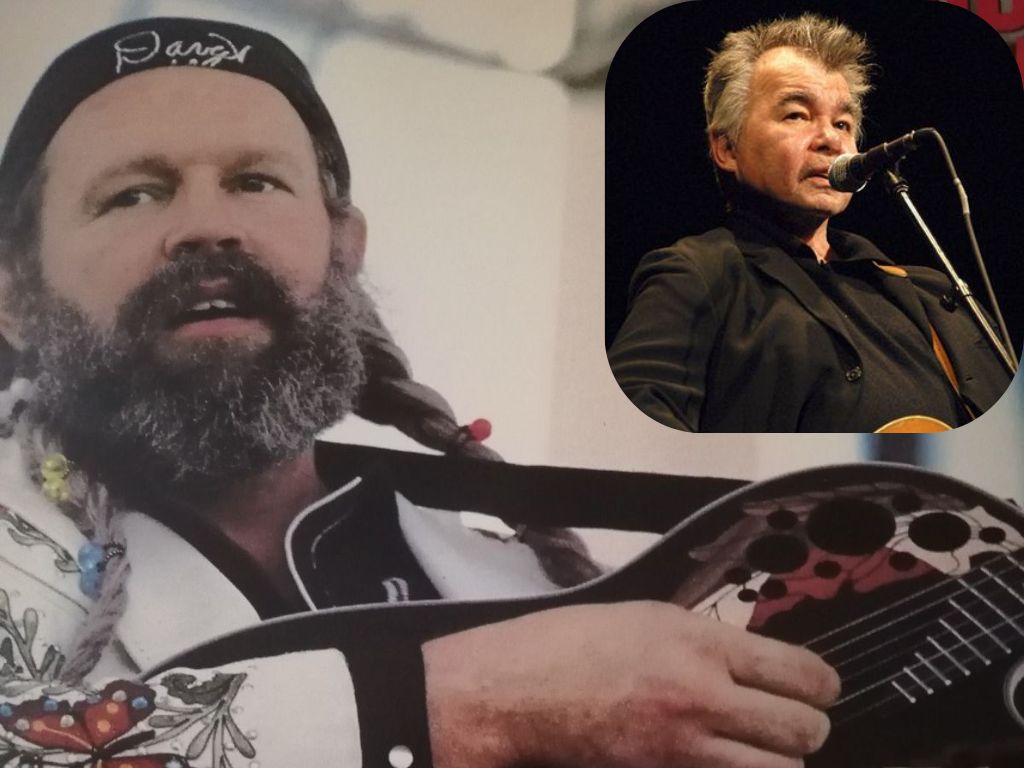

This album, issued on Columbia Records, reached #38 on the U.S. country albums chart upon release. The titular track “Hello in There” is not Coe’s own composition, but a haunting, respectful cover of John Prine’s 1971 folk song. By placing Prine’s gentle lament at the heart of his record, Coe surprised some listeners: amid his outlaw swagger and rough-hewn originals, he also carried an artist’s deep capacity for empathy.

The Story Behind the Song

John Prine originally wrote “Hello in There” when he was barely 22, inspired by his work delivering newspapers to an old‑people’s home. He recalled how some of the residents would treat him as a nephew or grandson, though he was just the mailman. That memory remained with him, transforming into one of his most tender, unforgettable songs: a quiet meditation on loneliness, aging, and the human need simply to be noticed.

Prine himself said he modeled the emotional structure of the song after The Beatles’ “Across the Universe,” especially inspired by its echo and its sense of reaching out across distance. That echo becomes almost literal in the lyric’s refrain: “Hello in there, hello,” as though he is calling into a hollow log, into someone’s heart, into a place that seems forgotten.

Meaning and Emotional Significance

At its core, “Hello in There” is a deeply compassionate piece. The narrator describes himself and Loretta, his wife, once living in a modest city apartment, now left alone as their children have grown and moved away. There’s even a quietly devastating line: “We lost Davy in the Korean War … I still don’t know what for.” This loss, spoken without bitterness but with a kind of resigned sorrow, underscores how aging doesn’t just bring loneliness—it brings memories that wound as much as they comfort.

Prine’s imagery is simple but unforgettable: “old trees just grow stronger / and old rivers grow wilder every day,” he sings, pairing physical growth with the emotional swell of a lifetime. Yet, despite this strength, “old people just grow lonesome / waiting for someone to say, ‘Hello in there, hello.’”

In the final verse, the narrator challenges us—those who are younger or more mobile: when you see someone with “hollow ancient eyes,” don’t just look away. Speak. Acknowledge them. “Please don’t just pass ’em by … say, ‘Hello in there, hello.’”

This isn’t a scolding. It’s a humble call for connection. It’s Prine—and by extension Coe—reminding us that every life, even the quietest, deserves to be greeted, seen, honored.

Why David Allan Coe’s Version Matters

When Coe chose to put this song on his 1983 album, he did more than offer a cover—he offered his own reflection, from his vantage point as an outlaw country singer who had lived hard and carried scars. On the album Hello in There, he divides the record into two conceptual halves—a “Country Side” and a “City Side” and places “Hello in There” on the City Side. In doing so, he seems to be drawing a bridge between his raw outlaw roots and a quieter, more introspective world.

Critics noted that Coe’s interpretation of the song was especially moving: AllMusic’s Thom Jurek said that Coe’s voice “turns the lyric inward, like a reflection in a mirror.”

While Coe contributed four original songs to the album, his performance of Prine’s song stands out as a moment of genuine vulnerability and empathy.

Reflection and Legacy

For an older listener, or anyone who has watched loved ones age, “Hello in There” feels like a gentle reminder—and maybe a little ache. It’s about noticing the ones who’ve lived full lives, even if they now seem quiet or invisible. When Coe sang it, he passed on Prine’s message: that respect for our elders is not nostalgic ornamentation, but a moral necessity.

In the context of Coe’s own life and career, the song also reveals his complexity. Yes, he was an outlaw, a rebel—but he was also someone who understood loneliness, loss, and the poetry in small, human moments. By titling his album after this song, Coe signalled to his listeners that beneath the grit he carried, there was a heart that beat to stories of memory, aging, and quiet longing.