A Lost Weekend in Juarez: The Price of Bohemian Indulgence

Ah, the 1960s. For those of us who remember them, the era feels like a shimmering, intoxicating mix of profound idealism and gritty realism. And few songs capture that stark contrast quite like Bob Dylan’s “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues.” While the original, which appeared on his groundbreaking 1965 album Highway 61 Revisited, didn’t chart as a single in the major US or UK markets, its impact was immediate and enduring, cementing its status as a cornerstone of the burgeoning folk-rock movement. It was a song that spoke in a cryptic, poetic language, perfectly tuned to the weary, searching soul of a generation wrestling with newfound freedoms and the crushing weight of disillusionment.

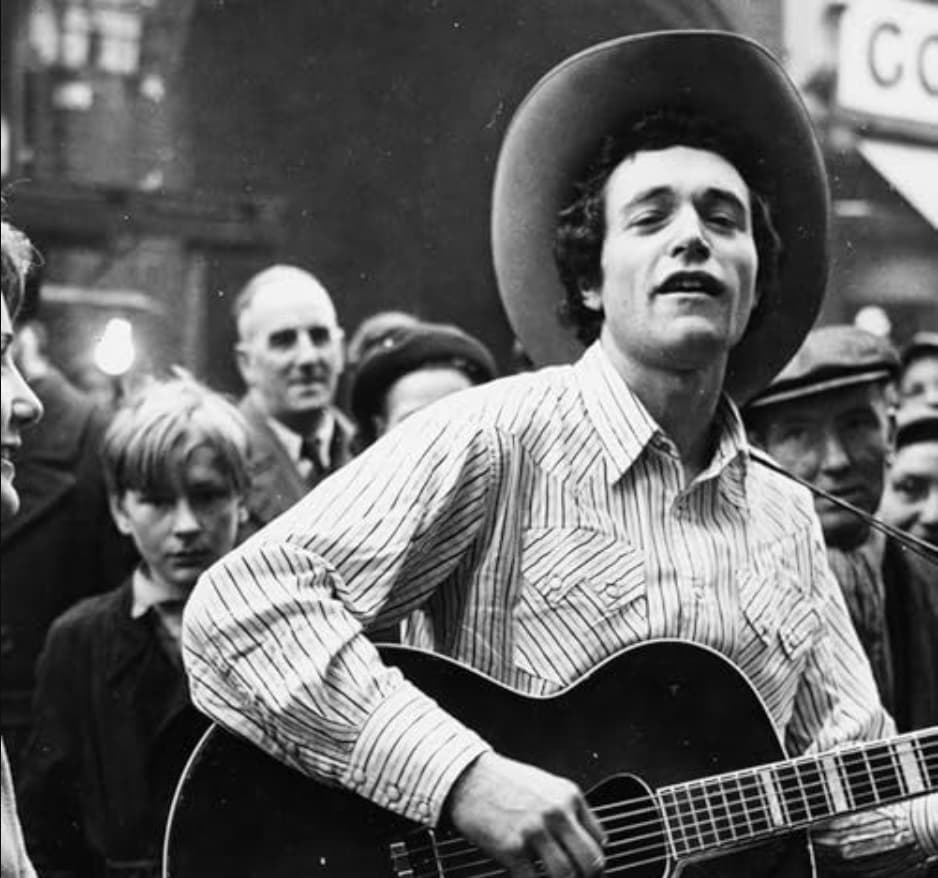

Yet, as we look back, there’s a particular cover version that stands out, not for its popularity, but for its sheer, authentic gravitas: the 2007 recording by the legendary folk troubadour Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. This performance, included on the soundtrack for the film I’m Not There, is a masterclass in lived experience. When Elliott sings those weary, word-drunk lines, you don’t just hear a song; you hear the dust of a thousand roads, the echo of countless late-night, smoke-filled rooms, and the hard-won wisdom of a man who has genuinely seen it all.

The story behind the song, originally penned by Dylan, is a nightmarish, evocative descent into the underbelly of Juarez, Mexico, a notorious border town. It’s a six-verse epic, chorus-less and unrelenting, that tracks a narrator’s lost weekend. The lyrics paint a vision of squalor and moral compromise: amidst the “sickness, despair, whores and saints,” the narrator encounters corrupt authorities, loose women named “Sweet Melinda” and “Saint Annie” who promise salvation but deliver only emptiness (“She takes your voice and leaves you howling at the moon”), and the general psychic drain of excess. The whole journey is a desperate search for something—pleasure, meaning, oblivion—that ultimately ends in utter defeat. The most famous line, a declaration of surrender, is the core meaning of the song: “I’m going back to New York City, I do believe I’ve had enough.” It’s the ultimate hangover cure, the exhausted decision to escape the decadence before it fully consumes you.

For older readers, the true magic of Elliott’s rendition lies in its connection to the very roots of American music. Ramblin’ Jack Elliott was a genuine link to the past—a self-proclaimed disciple of Woody Guthrie and a contemporary of the Greenwich Village folk scene that spawned Dylan himself. His version of “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” isn’t just a cover; it’s a passing of the torch, a testament to how the blues idiom can take a story of modern, Beat-influenced despair and ground it in a tradition of travel, hardship, and the weary, philosophical resignation of the rambling man. The song is laden with literary references, too—echoes of Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano and Jack Kerouac’s Desolation Angels, cementing its place as a cornerstone of the ’60s artistic and counter-cultural dialogue. It’s a song that proves that sometimes, the most profound experiences are found at the ragged edge, but true enlightenment comes from the simple, nostalgic desire to return home.