A joyful tribute to the winding roads and open skies of song

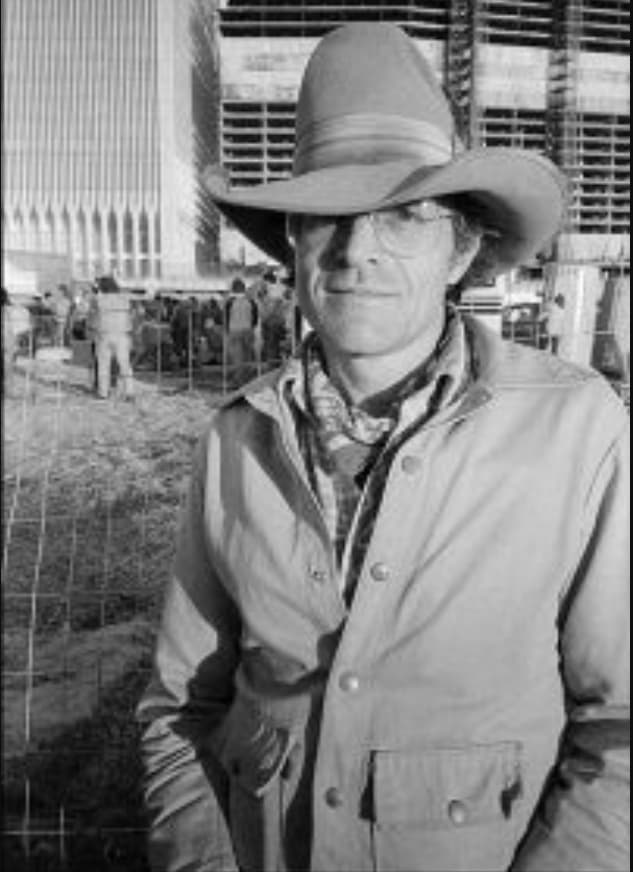

In the gentle strum of the guitar and the carefree hum of kazoo, the song “San Francisco Bay Blues” as interpreted by Ramblin’ Jack Elliott stands as an invitation—an invitation to drift, remember, and connect with something larger than ourselves.

When we speak of this version of the song, several facts emerge swiftly: the original composition was by Jesse Fuller, who first recorded it in 1954 and released it in 1955. Ramblin’ Jack Elliott included the tune on his 1958 album Jack Takes the Floor, where the song opened the record. The album was released in Great Britain in June 1958. As for chart positions, there is no reliable record that this particular rendition reached mainstream charts upon its release, which is not unusual for folk recordings of that era—they often circulated in live performance and word‑of‑mouth rather than through populist chart mechanics.

What makes this recording extraordinary is the story behind it. Elliott absorbed the song from Fuller. As one writer notes:

“It became a folk revival standard largely due to Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, who learned it from Fuller during a swing through the Bay Area and played it regularly.”

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the folk revival in America and Britain was gathering strength. Through the lens of Elliott’s performance, the song became a kind of touchstone—not simply for the sound of acoustic strings and kazoo, but for a way of life: the rambling troubadour, the open highway, the longing for connection.

Why does the song resonate so deeply? On the surface, its lyrics speak of leaving the city by the bay, heading out on the road, missing someone, and longing for home. But for the listener with a lifetime behind them, there’s something richer: it’s a reflection on journeying, on the inevitability of change, on the way the heart refracts all that movement into memory. When Elliott sings of “the San Francisco Bay / I’m gonna take me away,” you feel not only the geography, but the yearning for a place to belong, the recognition that the world is vast—but so is the heart.

Elliott’s interpretation brings a warmth and informality—his voice carries the dust of the road, yet it retains a kindness, an inviting tone. The instrumentation is simple: guitar, maybe kazoo, maybe a harmonica—elements that remind us of folk’s roots in the everyday. The modest equipment, the unblemished sincerity—that’s part of the charm. In an age where production can polish everything to luminosity, this recording whispers to us: here is one man, his instrument, his voice, and a story.

For older listeners, perhaps those who lived through the folk revival or heard it on crackling radios in living rooms, this song evokes a time of rediscovery. The 1950s and early 1960s held something of a crossroads: the post‑war promise, the shifting cultural tides, the yearning for authenticity. Elliott’s “San Francisco Bay Blues” lands right in the middle of that—neither flashy nor contrived, but abiding, like an old friend’s greeting.

Moreover, the song holds a social dimension. The original Fuller version—with its kazoo solo, its one‑man‑band spirit—was, in its way, a statement: music needn’t be grandiose to be meaningful. Elliott embraced that, and carried it onward during his career of sharing songs, stories, tradition. When this recording found its place on “Jack Takes the Floor”, it helped bridge American folk roots with British and European audiences, fueling the revival across the Atlantic.

The meaning of the song, then, becomes multi‑layered: it’s a personal rumination on travel and return; it’s a cultural artifact embedded in a folk revival movement; it’s a musical handshake across generations. For someone who has turned many seasons, that kind of song is a mirror: you listen and you hear your younger self, your older self, and everything between.

In reflecting on San Francisco Bay Blues, be aware that you’re not simply hearing a melody—you’re invited to lean back into memory, to recall journeys you’ve taken (both literal and emotional), to feel the prickle of nostalgia mixed with gratitude. And when the guitar finishes its last gentle chord, you’re left with the soft whisper of time passing and the enduring echo of a song that refuses to fade.

So take a deep breath, listen closely, and allow the voice of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott to carry you—maybe not to the bay itself, but to that place inside yourself where songs become companions, memories become melodies, and the simple act of listening becomes an act of remembering.