The Unexpected Divine Disco: A Tale of Creative Rebirth and Celestial Dance

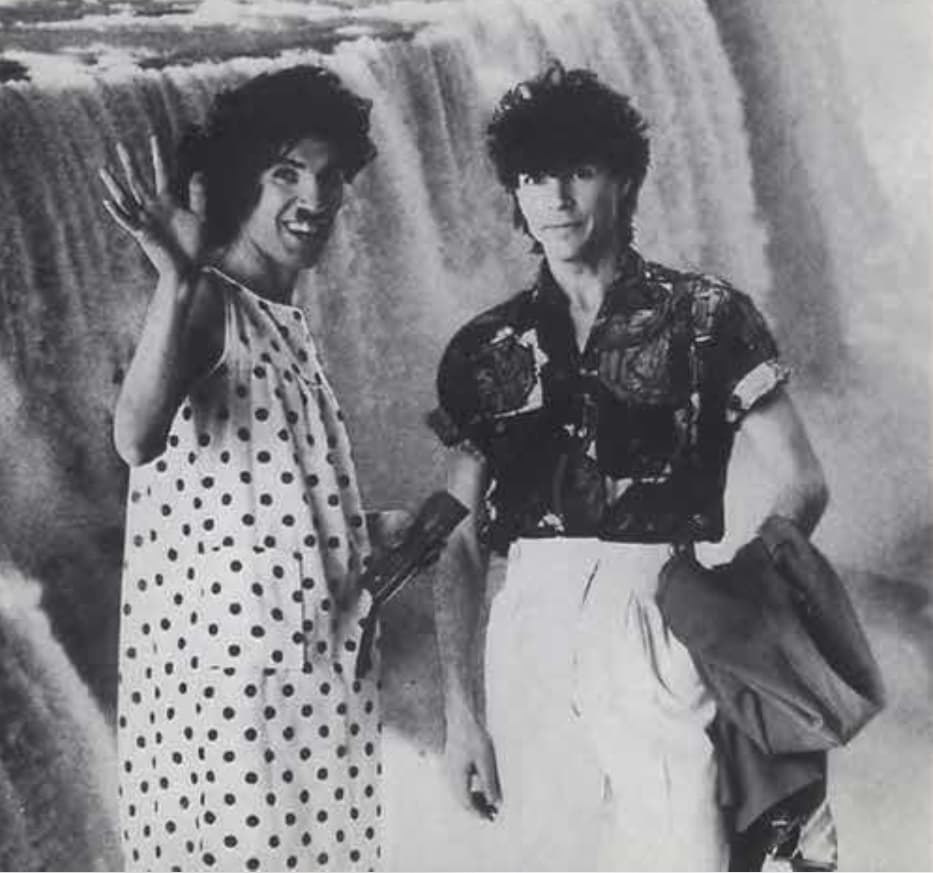

Ah, the late 1970s. For many of us, it was a time of seismic shifts in sound, a bridge between the grandiosity of rock’s golden age and the shimmering, mechanical future of electronic music. And right there, straddling that divide with their trademark mix of intellectual whimsy and pure pop genius, were the brothers Ron and Russell Mael, better known as Sparks. After a period of relative commercial disappointment following their glam-rock peak, they executed one of the most brilliant and bold reinventions in music history with the 1979 album No. 1 in Heaven.

The track “Here in Heaven” is not one of the singles, but it’s an essential heartbeat of this remarkable album. The record’s biggest hits, “The Number One Song in Heaven” and “Beat the Clock,” were charting successes; the former reached No. 14 in the UK Singles Chart and No. 5 on the Irish Singles Chart. While “Here in Heaven” itself was never released as a single and therefore did not have its own chart position, it is part of an album that fundamentally changed Sparks’ trajectory and influenced a generation of synth-pop pioneers.

The story behind this era is fascinating. Facing a waning interest in their guitar-driven rock, the Mael brothers took a colossal leap of faith, traveling to Munich to collaborate with disco maestro Giorgio Moroder, the man who practically invented the genre’s futuristic, synthetic sound with Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love.” This partnership resulted in an album recorded using only synthesizers and drums—a stark, brave departure from their past work. “Here in Heaven” encapsulates this transition perfectly.

In its meaning, the song is classic Sparks: an absurd and poignant narrative wrapped in an irresistible beat. The Maels often use surreal scenarios to explore profoundly human emotions. “Here in Heaven” tells a bizarre yet deeply melancholic story of a lover who has died and is now in heaven, utterly consumed by the memory of the mundane, everyday life he shared with his partner on Earth. He finds the divine beauty of the afterlife—the angels, the golden light—meaningless without the trivial comfort of his earthly relationship. The lyric “I miss you in the shower, and I miss you in the street, I miss you in your dressing gown, and in your worn out shoes” is a brilliant, emotional punch, using the most ordinary details to express extraordinary grief. The irony is palpable: he’s surrounded by paradise, yet all he yearns for is the sweet, imperfect banality of his previous life. It’s a beautifully meta commentary on longing, suggesting that heaven for one person might simply be the life they lost.

For those of us who remember this period, the song evokes a particular nostalgia. It’s the sound of a late-night drive, the glowing reds and yellows of the dashboard lights reflected in rain-slicked streets, a mood that’s both exhilaratingly modern and deeply wistful. The track has that signature Moroder propulsion—a hypnotic, motorik bassline and relentless electronic beat—that contrasts so dramatically with Russell Mael‘s highly theatrical, yet heartbreakingly sincere, vocal delivery. It wasn’t just music; it was a cultural moment, proving that rock musicians could embrace the new sound of disco and electronics without sacrificing their intelligence or their unique, darkly humorous soul. It’s a testament to the Sparks‘ genius that they could take such a stark, cold sound palette and imbue it with so much warmth and emotion. It is a true cult classic, a song that rewards the listener with both an invigorating dance floor rhythm and a quiet tear.