A Meditation on Time, Regret, and the Quiet Grace of Survival

When Bruised Orange (Chain of Sorrow) was released in 1978 as the title track of John Prine’s album Bruised Orange, it did not storm the pop charts. It was never meant to. The album itself reached No. 98 on the Billboard 200, a modest position by commercial standards, yet a testament to Prine’s steady, loyal following. By that time, John Prine had already established himself as one of America’s most literate and compassionate songwriters, admired by peers more than by radio programmers. Chart numbers, in this case, tell only a fraction of the story. The true measure of this song lies in its endurance and in the way it quietly inhabits the heart.

Released on Asylum Records, the album marked a renewed creative clarity for Prine after several uneven commercial years. Produced by Steve Goodman, a dear friend and fellow songwriter, Bruised Orange was a return to the observational storytelling that first defined Prine’s 1971 debut. In many ways, this record reaffirmed what artists such as Kris Kristofferson and Bob Dylan had long recognized: Prine was a writer of rare humanity.

The song “Bruised Orange (Chain of Sorrow)” opens with one of the most deceptively simple images in American songwriting:

“My heart’s in the ice house, come hill or come valley…”

From the first line, we are placed inside a landscape that feels both rural and internal. The imagery of orchards, highways, and Midwest skies evokes the American heartland — not as postcard nostalgia, but as lived terrain. Prine, born and raised in Illinois, understood that region not as myth, but as memory.

The phrase “bruised orange” itself is quietly brilliant. It suggests something once vibrant and whole, now damaged but not destroyed. A bruise does not erase sweetness; it merely marks it. That metaphor carries the entire emotional weight of the song. The “chain of sorrow” is life’s accumulation of small disappointments, accidents, and quiet losses — not dramatic tragedies, but the steady toll of time.

There is a story behind the song that deepens its resonance. Prine once mentioned that the song was inspired, in part, by an actual roadside memorial he saw after a car accident. That fleeting, almost anonymous human loss lingered with him. The lyric, “You can gaze out the window, get mad and get madder / Throw your hands in the air, say, ‘What does it matter?’” feels less like a rhetorical flourish and more like a confession. It speaks to that universal moment when frustration collides with helplessness.

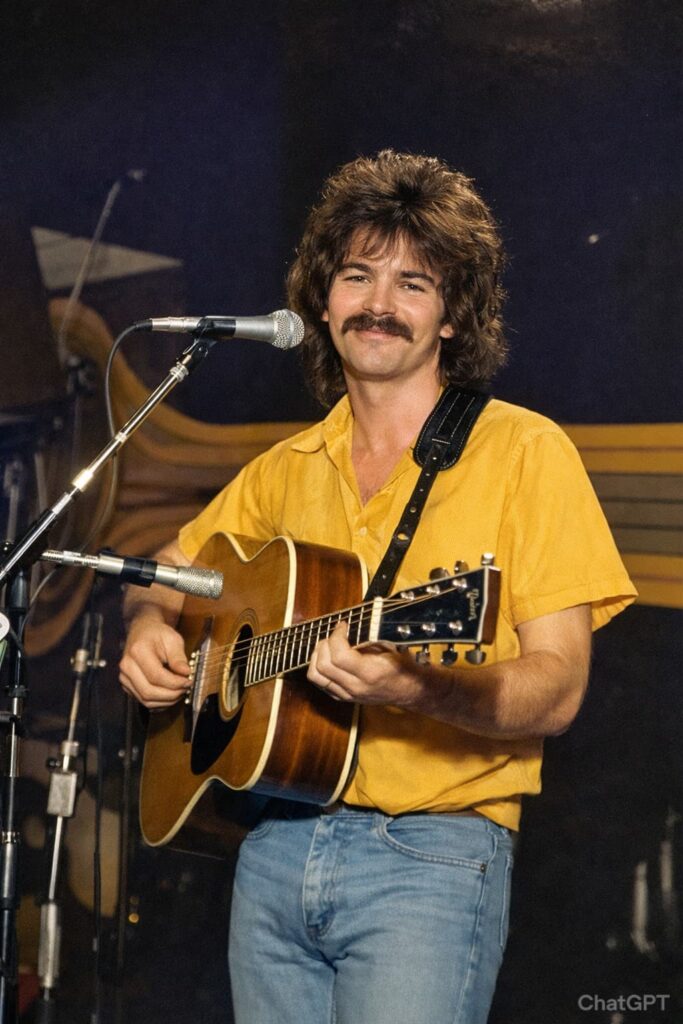

Musically, the arrangement is restrained — acoustic guitar, subtle rhythm, and Prine’s conversational vocal phrasing. His voice was never polished in the conventional sense. It carried the grain of lived experience. By 1978, that voice had matured, slightly worn, perfectly suited to the song’s reflective tone. Unlike the soaring anthems of arena rock that dominated the late 1970s, this track invites stillness. It rewards attentive listening.

Within the broader context of Prine’s career, Bruised Orange stands as one of his most cohesive albums, alongside earlier landmarks like John Prine (1971). The 1978 record also includes “Sabu Visits the Twin Cities Alone” and “That’s the Way That the World Goes ’Round,” songs that blend humor and melancholy in equal measure — a balance Prine mastered like few others.

The meaning of “Bruised Orange” ultimately circles back to endurance. The song does not offer grand solutions or sentimental redemption. Instead, it suggests acceptance — a recognition that life’s marks are evidence of having lived fully. The bruises become proof of sweetness once held, once tasted. There is grace in that acknowledgment.

Over the decades, the song has grown in stature. It may not have been a Top 40 hit, but it became a cornerstone of Prine’s live performances. Audiences sang along not because it dominated radio waves, but because it mirrored private thoughts. When Prine passed away in 2020, many returned to this track as a reminder of his gentle wisdom.

Listening now, one senses that John Prine was never writing for the charts. He was writing for the long road — for people driving at dusk, for those reflecting on decisions made and chances missed, for anyone who has stood at the edge of regret and chosen to keep going.

In the end, “Bruised Orange (Chain of Sorrow)” is less about sorrow than about resilience. The bruise fades, but the fruit remains. And so does the song.