Song of Love — a reflective hymn to love’s contradictions, written in an age that questioned everything

There is a particular kind of stillness that surrounds “Song of Love” by Stephen Stills — not silence, but the calm that arrives after years of searching, when questions no longer demand urgent answers. The song appears on Manassas, the ambitious double album released in 1972, a work that captured Stills at a crossroads: no longer the restless young voice of Buffalo Springfield, no longer entirely defined by the collective harmony of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, but a songwriter standing alone, willing to look inward and outward at the same time.

To place the song properly, it helps to begin with the album itself. Manassas was a bold statement, sprawling in scope and sound, blending rock, folk, blues, country, and Latin influences into a unified whole. Upon its release, the album was met with both critical respect and commercial success, reaching the Top 5 on the Billboard album chart — a confirmation that Stills’ vision still resonated deeply with listeners. “Song of Love” was never released as a single, and it never chased chart positions, yet its quiet presence within the album has given it a long, dignified life.

What sets “Song of Love” apart is its refusal to define love narrowly. This is not a love song bound to one face or one memory. Instead, it feels like a meditation — part confession, part observation. The lyrics move between tenderness and unease, suggesting that love is both a refuge and a responsibility, a source of comfort and a mirror reflecting the world’s imperfections. In the early 1970s, when ideals were being tested and certainties dissolved, this kind of songwriting felt honest, even necessary.

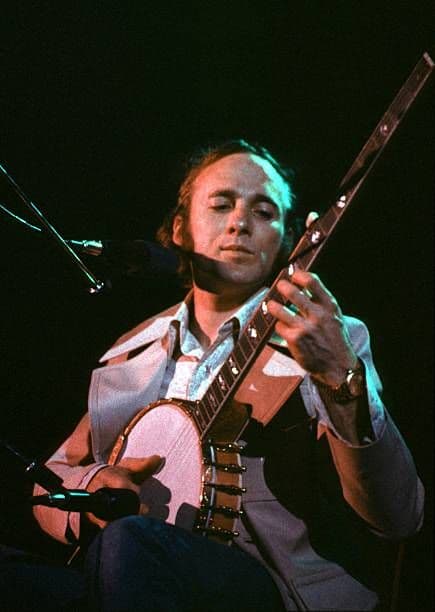

Stills sings not as a preacher or a dreamer, but as a man who has seen love survive pressure. His voice carries warmth, yet there is an edge of realism beneath it — an understanding that love does not exist in isolation from conflict, loss, or doubt. The arrangement supports this feeling beautifully: understated guitar lines, measured rhythms, and a sense of space that allows the words to breathe. Nothing rushes. Nothing demands attention. The song unfolds at its own pace, trusting the listener to meet it halfway.

For those who remember the era when Manassas first arrived, “Song of Love” often evokes more than just music. It brings back rooms filled with conversation and cigarette smoke, record players spinning late into the night, and a time when songs were listened to carefully, almost reverently. This was music meant to be absorbed, not consumed — music that lingered long after the needle lifted.

Yet the song’s power has only grown with time. Heard decades later, it carries a different weight. What once sounded like youthful reflection now feels like wisdom gently earned. Love, as Stills presents it, is not idealized; it is accepted in full — with its promises and its limitations. There is comfort in that acceptance, especially for listeners who have loved deeply, lost quietly, and continued on with grace.

In the broader arc of Stephen Stills’ career, “Song of Love” stands as a reminder of his depth as a writer. He was never content with surface emotion. Even in moments of beauty, he searched for truth, and even in truth, he allowed room for tenderness. This song does not shout its importance. It waits patiently, confident that those who need it will find it.

And when they do, they may recognize themselves within it — the hopes once held, the compromises made, the love that endured in unexpected forms. “Song of Love” becomes less a product of its time and more a companion across years, whispering that love, however imperfect, is still worth singing about.