A quiet, unhurried hymn to freedom, “Me and Bobby McGee” becomes something entirely different when filtered through the gentle, introspective voice of Gordon Lightfoot—a version rooted not in fireworks, but in the soft ache of roads remembered.

When Gordon Lightfoot recorded “Me and Bobby McGee” in early 1968 for his album Did She Mention My Name?, the song had not yet become the cultural monument it would later be. It hadn’t climbed any charts, because Lightfoot’s take was never released as a single, and therefore held no chart position at the time of its debut. But what it carried—quietly, without fanfare—was the first fully realized interpretation of Kris Kristofferson and Fred Foster’s wandering ballad. Long before Janis Joplin electrified it and before it became a mythic anthem of the 1970s, Lightfoot framed the song as a folk narrative—closer to a journal entry than a performance—offering listeners a glimpse into the emotional marrow the writers had intended.

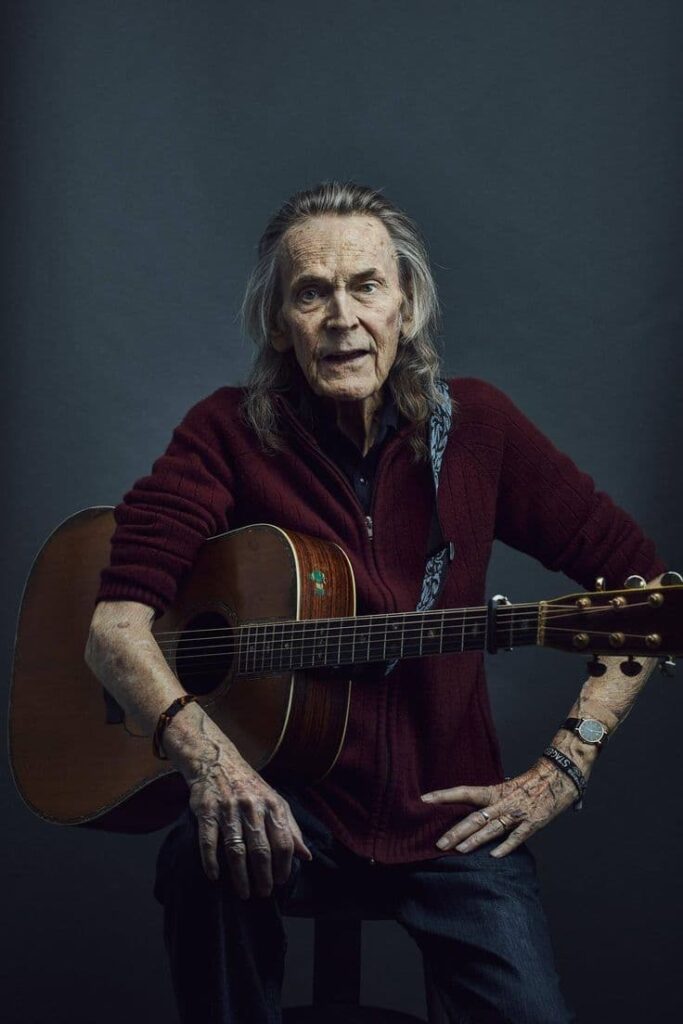

For Lightfoot, the song fit naturally into his world. By the late ’60s he had become a voice of pastoral folk, an artist capable of pulling entire landscapes into a single melodic line. In his hands, “Me and Bobby McGee” becomes less a tale of restless travel and more a meditation on the quiet companionship two weary souls find along the way. While other versions leaned into grit, heartbreak, or flamboyant passion, Lightfoot gave us warmth—something worn-in, like the last half-hour of a long drive at dusk. His delivery carries the weight of memories not yet old, but already slipping through the fingers.

The story behind “Me and Bobby McGee” itself is steeped in the bittersweet spirit of American songwriting. Inspired partly by the idea of a pair of drifters unwinding their lives across highways and small towns, Kristofferson imagined love not as permanence but as the soft light that passes through the day before it leaves. “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose” is often quoted for its philosophical punch, but in Lightfoot’s reading, that line feels less like existential despair and more like something spoken during a quiet evening on the road, when one begins to understand that letting go and holding on sometimes feel eerily similar.

Lightfoot’s interpretation highlights the emotional geography of the song. His voice—steady, reflective, unhurried—places Bobby and the narrator not in dramatic motion but in a kind of suspended moment: two travelers sharing cigarettes, laughter, and stories while the countryside rolls past the windows. There’s no rush, no frantic chase, no roaring crescendo—just the earned calm of people who know that closeness is a temporary blessing. And that, perhaps, is why so many who discover Lightfoot’s version later in life often grow attached to it. It returns them to memories of roads once taken, of long conversations that felt eternal, of the strange tenderness that arises between people traveling the same direction for a little while.

Though overshadowed by later recordings, Lightfoot’s rendition remains one of the most emotionally faithful interpretations in the song’s vast lineage. It preserves the composition’s bones—its folk heart, its wandering spirit, its soft melancholy—and presents them without theatricality. You can hear the gravel of forgotten highways, the hush of a bus at night, and the gentle shift in someone’s voice when they recall a person who mattered, even if only for a chapter.

In many ways, Gordon Lightfoot’s “Me and Bobby McGee” stands as a reminder of what the song originally was before fame transformed it: a tender, human story of two people passing through the world together until life, as it always does, carried them apart. And in his quiet phrasing, you can feel him honoring that simple truth—holding it carefully, like something fragile—so that listeners, decades later, might close their eyes and remember the roads that once carried them too.