A Mirror to America’s Heart: Choctaw Bingo by James McMurtry

Choctaw Bingo is not just a song — it’s a vivid, raw snapshot of a sprawling, eccentric American family, tracing its roots through backroads, backstories, and broken dreams.

James McMurtry’s “Choctaw Bingo”, from his 2002 album Saint Mary of the Woods, is one of his most beloved and hauntingly honest pieces. Although it didn’t blaze on mainstream charts as a pop single — McMurtry’s work has always lived more in the realm of Americana than Top 40 radio — the song has secured a deeply rooted place in his catalog and in the hearts of listeners. The song has become something of a signature anthem at his live shows, where it is often performed, capturing audiences with its vivid storytelling.

The Story Behind the Song

At its heart, Choctaw Bingo is a narrative ballad told through alternating verses and instrumental breaks — there’s no traditional chorus. The story is a rambunctious, wry family reunion, somewhere in Oklahoma, at the homestead of “Uncle Slaton.” McMurtry conjures a cast of colorful, flawed characters: Slaton, aging but “still pretty spry,” living with his “Asian bride,” maintaining an Airstream trailer and a Holstein cow, and still distilling moonshine because his whiskey doesn’t move.

There’s also Cousin Roscoe, Slaton’s oldest son from a second marriage, driving in from Illinois, reared in East St. Louis — a contrast of worlds that underscores how layered and messy this family is. Then there’s Bob and Mae, from a small town by Lake Texoma, where Bob coaches football but seems on the brink of struggle. And finally Ruth-Anne and Lynn, wild second cousins from Baxter Springs, Kansas — McMurtry doesn’t shy away from taboo or eccentricity in his storytelling.

Throughout, there’s a sense that this reunion is not just about kinship, but survival: Slaton sells land, maybe with shady motives; he cooks crystal meth when his shine won’t pay; he finances lots to people “with no kind of credit” because he knows they’re “slackers.” The song probes the tensions of economic hardship, moral ambiguity, and generational legacy.

Musically, McMurtry borrows from the Chuck Berry playbook: the melody, tempo, and even the structure evoke Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me.” This isn’t a straightforward folk lament — it’s honky-tonk rock, delivered with urgency and wit.

The Meaning & Significance

What makes Choctaw Bingo so powerful is how it holds up a mirror to everyday dysfunction, pride, and tragedy. It’s a portrait of a country that built itself on myth and struggle, but where the seams are worn and reality doesn’t always shine.

McMurtry doesn’t moralize. Instead, he tells stories that let the listener feel the contradictions: love and resentment, laughter and pain, tradition and crime. The song becomes a kind of social commentary, wrapped in family lore, that reflects on economic decline, the lure of easy money, and the shadow economies that sometimes emerge when conventional opportunities dry up.

One compelling interpretation is that Choctaw Bingo resonates as a uniquely American anthem of resilience, capturing the grit and humor that help people survive in difficult times.

Legacy & Performances

Over the years, Choctaw Bingo has become something of a live staple for McMurtry. His fans often say it’s the moment in concert when the room comes alive — people dance, holler, and hang on every verse. A nearly ten-minute live version even appears on his album Live in Europe.

The song has also inspired others: artists in the Americana scene have covered it, demonstrating how McMurtry’s vivid storytelling reaches beyond his own fan base.

Why It Matters (Especially Now)

For those who remember a different America — where small towns and family ties held meaning, but where economic hardship was just beneath the surface — Choctaw Bingo is deeply resonant. It’s not a nostalgic fantasy; it’s a bittersweet, gritty recollection of people doing their best in a world that doesn’t always reward honesty or hard work.

When we listen, we’re invited into a smoke-filled, whiskey‑scented reunion: to hear the laughter, but also the regret. To know that Uncle Slaton is “too mean to die,” that Roscoe’s journey is more than just a road trip, and that in the end, every character is bound by blood — for better or worse.

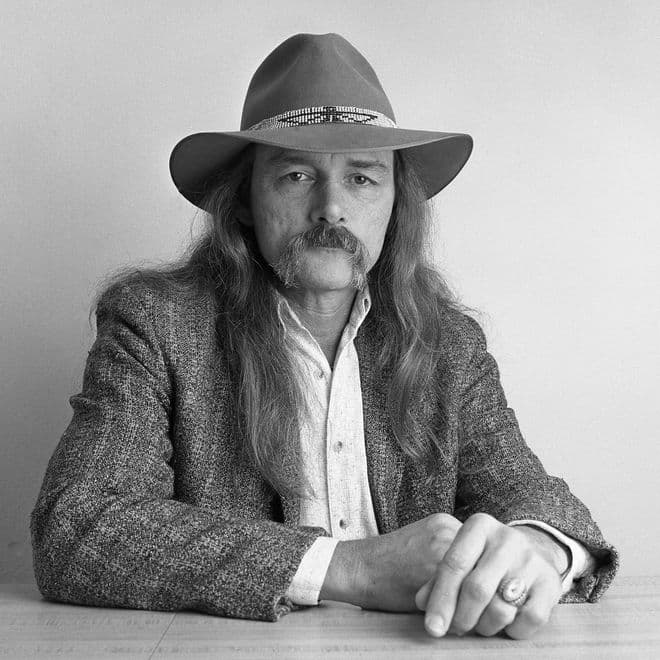

James McMurtry, son of novelist Larry McMurtry, clearly inherited a storyteller’s gift. In Choctaw Bingo, he blends that literary heritage with raw Americana, giving us a song that feels like a short story, a confession, and a celebration — all rolled into one.

Listening to Choctaw Bingo today, we reconnect with the past: the dusty highways, the tough choices, the laughter that echoes through generations. It reminds us that even in the roughest corners of our lives, there is a strange kind of beauty — and someone, in a distant trailer or by a jugline, is still calling “We’re gonna have us a time.”