The Poetic Empathy of a Solitary Soul: Don McLean’s Timeless Tribute to a Misunderstood Masterpiece

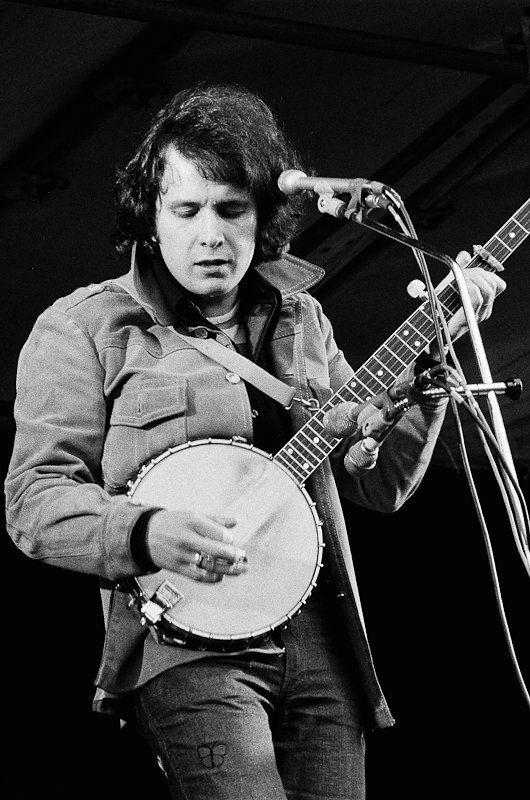

There are songs that capture a moment in time, and then there are those rare compositions that reach across generations, touching the eternal human ache of being misunderstood. Don McLean’s exquisite ballad, “Vincent,” is one such masterpiece. Released in 1972 as the second single from his landmark album, American Pie (1971), this song is much more than a musical ode to a painter; it is a profoundly empathetic elegy for the unappreciated genius, the sensitive soul crushed by a world that refused to see his light. Its gentle, haunting melody, carried primarily by acoustic guitar, a subtle accordion, marimba, and violin, became an instant comfort to millions.

The song was an enormous international success, particularly in the UK, where it soared to Number 1 on the UK Singles Chart and stayed there for two weeks in June 1972, a major achievement. While its massive predecessor, the title track “American Pie,” stalled at Number 2 across the Atlantic, “Vincent” peaked at a respectable Number 12 on the US Billboard Hot 100 chart and climbed as high as Number 2 on the Easy Listening chart—a true testament to its universal, soothing appeal. It remains one of McLean’s most enduring and beloved works.

The creation of “Vincent” is a poignant tale of inspiration. Don McLean was working a gig, singing in school classrooms in the autumn of 1970, when he was reading a biography of the post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh. He was immediately struck by the tragedy of a man whose vibrant vision was met only with ridicule and rejection during his lifetime. The common trope of the painter as a “madman” bothered McLean deeply. As he later recounted, he felt compelled to write a song that argued Van Gogh was not simply “crazy,” but rather suffered from an illness—what we might now understand as a severe mental disorder—which made his suffering different from garden-variety “madness.” The painter’s profound sensitivity, he argued, made him a sane commentator on an insane world.

Sitting on a veranda with a printed reproduction of Van Gogh’s most famous work, The Starry Night, McLean penned the beautiful lyrics out on a paper bag. The opening line, “Starry, starry night,” immediately transports the listener into Van Gogh’s swirling, vivid world. The song cleverly weaves descriptions of several of the artist’s most recognizable paintings—the “flaming flowers that brightly blaze” perhaps referencing the Sunflowers, and the “swirling clouds in violet haze” directly pulling from The Starry Night—into a narrative that grapples with the painter’s isolation and his ultimate suicide. The lines, “Now I understand what you tried to say to me / And how you suffered for your sanity / And how you tried to set them free / They would not listen, they did not know how / Perhaps they’ll listen now,” are a direct, heartfelt lament for the artist’s unacknowledged genius, a cry that rings true for every artist who has ever felt ahead of their time or misunderstood. It’s a bridge built from one sensitive soul to another, stretching across the decades to offer the painter the recognition he deserved. For older readers, the song evokes a time when discussing mental anguish was still taboo, making McLean’s gentle empathy all the more moving and progressive.

“Vincent” is a reflection on the cruelty of the crowd’s indifference to beauty and truth, a simple folk melody that somehow manages to contain the full, vibrant spectrum of Van Gogh’s painted sorrow and splendor. It is a song that doesn’t simply tell you about the painter; it makes you feel the “darkness in my soul” that McLean himself was grappling with during a difficult period in his life, finding a kindred spirit in Vincent’s tragic story. It’s a nostalgic journey back to an era of pure, unvarnished songwriting that valued poetry and profound emotional resonance over slick production, reminding us that true art is often born from profound suffering, and that recognition, sadly, often comes too late.