A Heartbreaking Portrait of a Lost Soldier’s Homecoming

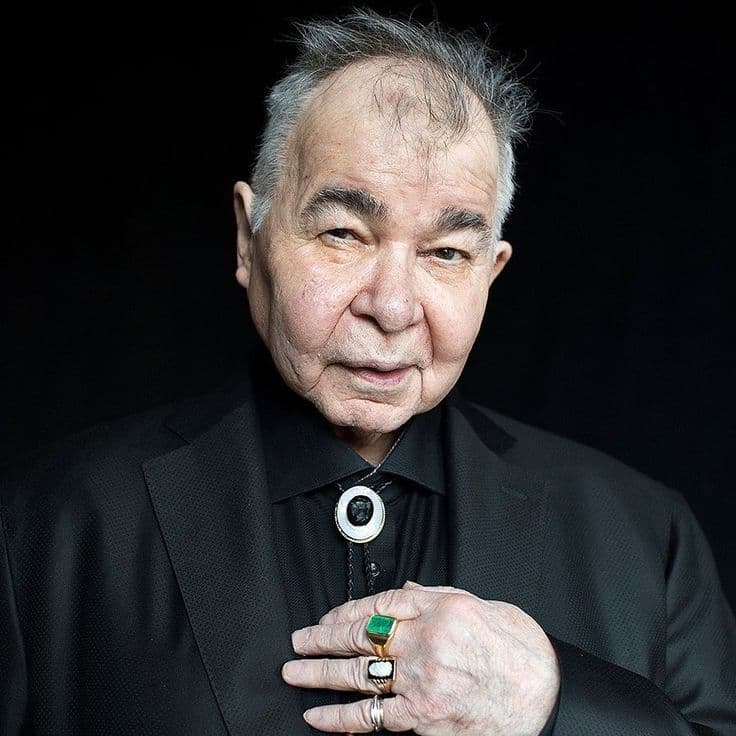

Ah, “Sam Stone”, a song that resonates with a profound and melancholic truth, paints a vivid picture of a Vietnam War veteran grappling with the invisible wounds of conflict and the devastating consequences of addiction. When this poignant narrative unfolded into our ears, courtesy of the remarkable John Prine, it climbed to a respectable position on the Billboard charts, peaking at number 72 in 1971. This wasn’t a chart-topper in the conventional sense, but its impact stretched far beyond mere numbers, embedding itself deeply within the hearts of listeners who recognized the raw humanity and tragic reality it portrayed.

The genesis of “Sam Stone” is as compelling as the song itself. John Prine, a young mailman at the time, had a remarkable gift for observing the world and translating its complexities into simple yet devastatingly effective lyrics. He drew inspiration for “Sam Stone” not from personal combat experience, but from the stories he heard and the faces he saw. He wove together fragments of different individuals he encountered – a friend’s brother-in-law who had returned from the war with a drug habit, the general atmosphere of disillusionment surrounding the Vietnam era, and the quiet suffering he sensed in the lives of ordinary people. In an interview, Prine mentioned that the character of Sam Stone was an amalgamation, a composite of several soldiers he had either known or heard about. This blending of realities lends the song a universal quality, making Sam Stone not just one man, but an archetype of the returning soldier struggling to reintegrate into a society that often failed to understand their burdens.

The beauty and the tragedy of “Sam Stone” lie in its unflinching portrayal of the aftermath of war. It doesn’t dwell on heroic battles or grand narratives; instead, it focuses on the quiet, internal battles fought long after the guns have fallen silent. The recurring line, “There’s a hole in Daddy’s arm where all the money goes,” is a stark and unforgettable image of addiction, a coping mechanism for the trauma that words often fail to express. The medals on Sam’s chest, symbols of his service and sacrifice, become ironic testaments to a system that honors the soldier in uniform but often abandons him upon his return. The lyrics speak of a man who “came home from Vietnam with a Purple Heart and a bad case of the goin’ home blues,” a line that encapsulates the deep sense of displacement and the struggle to find peace in a world that feels alien.

“Sam Stone” is more than just a song; it’s a narrative etched in empathy and understanding. It speaks to the invisible wounds of war – the psychological scars that linger long after the physical ones have healed. It touches upon themes of isolation, the difficulty of readjustment, and the devastating grip of addiction as a means of escape. The song doesn’t offer easy answers or a sentimental resolution. Instead, it presents a stark and honest portrayal of a life irrevocably altered by the experience of war.

Released on his self-titled debut album, “John Prine”, in 1971, “Sam Stone” quickly became a cornerstone of his early work and remains one of his most enduring and powerful songs. The album itself was a remarkable introduction to a songwriter of immense talent, filled with songs that were both deeply personal and universally relatable. Tracks like “Angel from Montgomery” and “Paradise” further cemented Prine’s reputation as a storyteller with a keen eye for detail and a profound understanding of the human condition.

Over the years, “Sam Stone” has been covered by numerous artists, a testament to its enduring power and its ability to resonate across different voices and generations. Each rendition brings its own nuances, but the core message of the song – the tragic cost of war on the individual – remains potent and unwavering. Listening to “Sam Stone” today still evokes a sense of profound sadness and a deep respect for those who have served and continue to struggle with the aftermath of their experiences. It serves as a poignant reminder of the human cost of conflict, a cost that often extends far beyond the battlefield and into the quiet desperation of a soldier’s homecoming. It’s a song that stays with you, a whisper of a life marked by sacrifice and shadowed by an enduring pain.