A gentle anthem of harmony that turned a children’s rhyme into a timeless call for unity

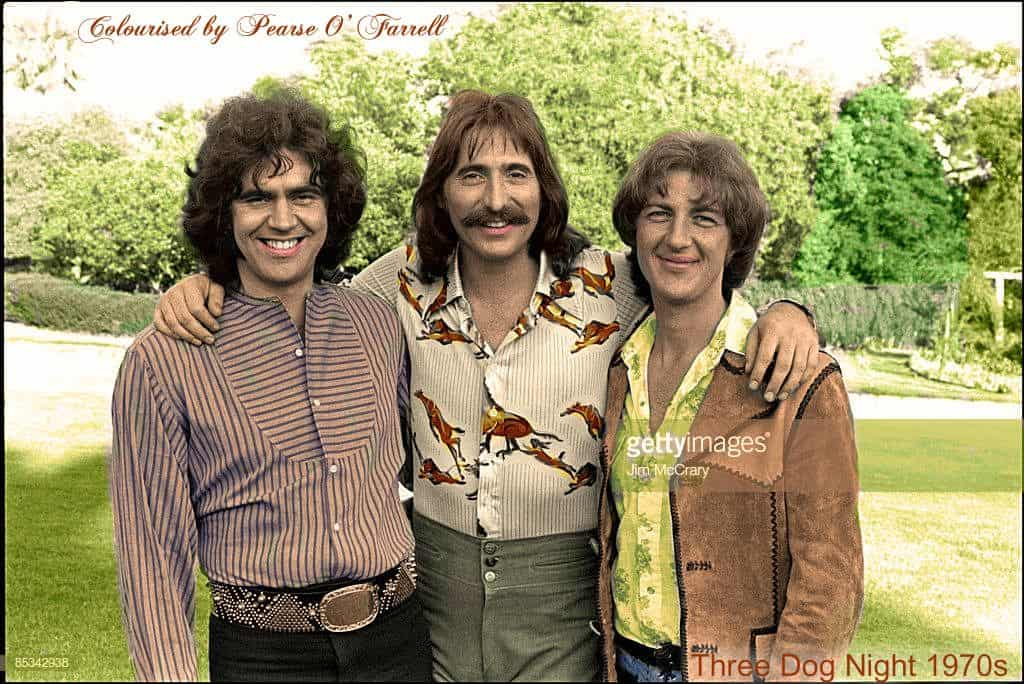

When “Black and White” was released by Three Dog Night in the late summer of 1972, it arrived quietly, almost modestly, yet it carried a message that would resonate far beyond its playful melody. In October 1972, the song climbed all the way to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, holding the top position for one week. It became the group’s final chart-topper in the United States, closing an extraordinary run that had already made Three Dog Night one of the most successful singles bands of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The song appeared on the album Seven Separate Fools (1972), a record released during a period of transition for the band. Musical tastes were shifting, radio was becoming more fragmented, and the easy dominance of hit-making pop-rock groups was no longer guaranteed. Yet “Black and White” cut through the noise with something deceptively simple: a tune that sounded like it could be sung by a classroom of children, but carried a meaning clearly aimed at the adult world.

Written by David I. Most, “Black and White” was inspired by a children’s rhyme he encountered in a classroom while teaching. That origin matters. The song’s verses, sung from the perspective of children learning about equality, avoid slogans and anger. Instead, they speak in clear, uncomplicated terms: “The ink is black, the page is white / Together we learn to read and write.” In an era still deeply marked by civil rights struggles, school desegregation debates, and cultural division, this simplicity felt almost radical. The song did not argue. It reminded.

Musically, Three Dog Night understood exactly how to serve that message. The arrangement is bright and uncluttered, built around a steady piano figure, gentle horns, and a buoyant rhythm that never overwhelms the lyric. Vocally, the band’s greatest strength—its rotating lead singers and rich group harmonies—comes to the fore. Rather than spotlighting a single voice, “Black and White” feels communal. Lines pass naturally from one singer to another, reinforcing the idea that the song belongs to everyone, not to an individual ego.

For listeners who had grown up with Three Dog Night hits like “Joy to the World,” “Mama Told Me (Not to Come),” and “One,” this song felt both familiar and different. Familiar in its melodic warmth and radio-friendly polish, but different in tone. There is no irony here, no wink to the audience. The band delivers the lyric with sincerity, trusting that the message does not need decoration. That trust paid off, especially with audiences who had lived through the turbulence of the previous decade and were ready, perhaps even hungry, for a moment of uncomplicated hope.

The cultural timing of “Black and White” also played a crucial role in its success. By 1972, many listeners were weary of confrontation. Protest songs had given way to reflection, and optimism, however fragile, felt necessary. The song’s chart-topping success suggested that a large audience still believed in the possibility of shared values, even if reality often fell short.

Looking back now, “Black and White” stands as more than just a late-career hit. It represents a closing chapter in Three Dog Night’s remarkable singles era and a reminder of how pop music can carry serious ideas without losing its accessibility. The song does not lecture; it invites. It asks the listener to remember a time when learning right from wrong felt clear, when fairness was not a political stance but a basic lesson.

For those who first heard it on AM radio in 1972, “Black and White” can still feel like opening an old schoolbook and finding a familiar drawing in the margins—slightly faded, perhaps, but still meaningful. Its message has not aged because it was never tied to a momentary trend. It speaks in the voice of memory, reminding us that some truths were once taught early, sung together, and believed without hesitation.