A Restless Heart Torn Between Roads and Roots

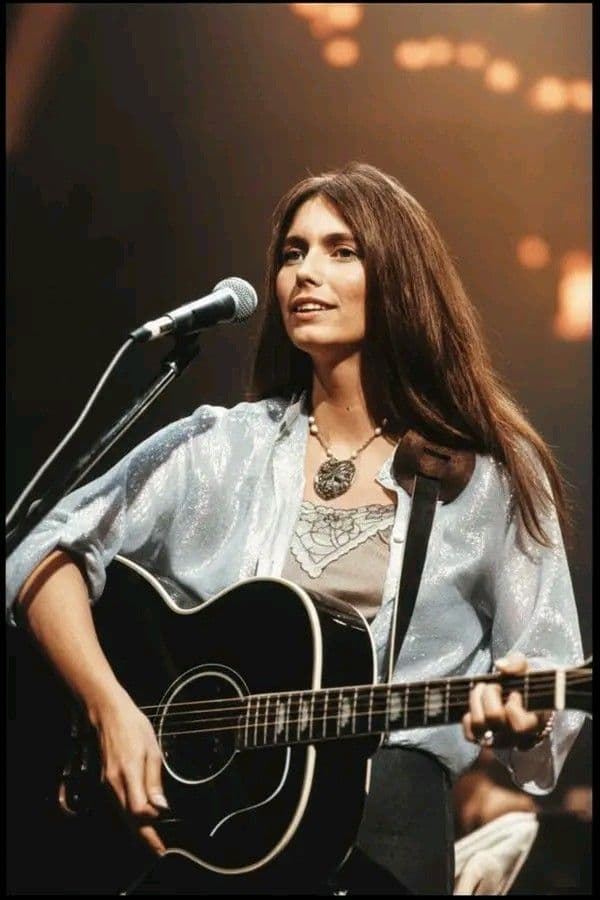

When “Tulsa Queen” – Emmylou Harris first arrived in 1977 as part of the landmark album Luxury Liner, it carried with it the pulse of the open highway and the ache of a woman forever chasing a restless dream. Though not released as a major single in the United States, the album itself reached No. 12 on the Billboard Top Country Albums chart, reaffirming Harris’s position as one of the most compelling voices in country music during that golden decade. The record also produced Top 10 country hits like “One of These Days” and “(You Never Can Tell) C’est La Vie”, situating “Tulsa Queen” within a collection that balanced honky-tonk drive and emotional introspection with rare finesse.

Written by Rodney Crowell—then a young songwriter and guitarist in Harris’s Hot Band—“Tulsa Queen” feels autobiographical even when it isn’t. It tells the story of a woman bound to a truck driver, circling the American heartland in an endless loop of departure and return. She is devoted, loyal, and yet unmistakably caught in the undertow of someone else’s wandering spirit. There is pride in her identity—she is the “queen” of Tulsa, after all—but there is also a subtle melancholy beneath that crown. It is not royalty that defines her; it is waiting.

In Harris’s hands, the song becomes something more than a narrative about life on the road. Her voice—clear as prairie wind, tinged with longing—transforms it into a meditation on love’s compromises. Unlike the fiery heartbreak of earlier classics she recorded with Gram Parsons, or the crystalline sorrow of songs like “Boulder to Birmingham”, “Tulsa Queen” is steadier, more grounded. It moves at the rhythm of tires against asphalt. The arrangement, driven by steel guitar and a supple rhythm section, evokes the hum of long-distance travel, yet Harris never lets the instrumentation overshadow the emotional center.

The story behind the recording is deeply entwined with the community she built around her. By 1977, Harris had already established herself with albums such as Pieces of the Sky and Elite Hotel, both critically acclaimed and commercially successful. Her collaboration with Crowell was particularly significant. He would later become one of Nashville’s most respected songwriters, but at that moment he was still a rising talent, and Harris’s decision to champion his work—“Tulsa Queen” among them—revealed her gift not only as an interpreter but as a curator of American songwriting. She had an uncanny instinct for songs that carried both narrative clarity and emotional undercurrents.

Lyrically, “Tulsa Queen” speaks to a universal tension: the pull between stability and wanderlust. The protagonist’s loyalty is unquestioned, yet the life she lives is defined by motion, not permanence. In that way, the song quietly reflects Harris’s own artistic journey. After the tragic death of Gram Parsons, she could have retreated into safety. Instead, she kept moving—touring relentlessly, refining her sound, blending traditional country with rock sensibilities. There is a mirror between artist and song: both standing tall, both shaped by the road.

The meaning of the song unfolds gently. On the surface, it is about devotion to a man who cannot stay still. Beneath that, it becomes a portrait of American life in the 1970s—an era when highways symbolized freedom, but also separation. The “queen” title suggests dignity, but also irony. She reigns in a kingdom defined by absence. Harris does not dramatize this; she allows it to breathe. That restraint is what makes the performance enduring.

Listening now, decades later, “Tulsa Queen” feels like a snapshot of a time when country music still carried the dust of small towns and the shimmer of neon truck stops. It belongs to a period when storytelling mattered more than spectacle. In Harris’s catalog, it may not be her most famous recording, but it stands as a testament to her interpretive depth. She had—and still has—the rare ability to inhabit a character completely, to let us see the horizon through her eyes.

In the broader landscape of classic country, “Tulsa Queen” remains a quietly powerful gem within Luxury Liner, an album that confirmed Emmylou Harris as both guardian of tradition and gentle innovator. It is not a song that shouts. It lingers. Like the memory of headlights fading into the distance, it reminds us that some loves are measured not in grand gestures, but in miles traveled together—and apart.