I Don’t Love You Much, Do I — when love speaks softly, truth cuts deepest

Few songs understand the fragile space between love and silence quite like “I Don’t Love You Much, Do I”, written by Guy Clark and recorded as a haunting duet with Emmylou Harris. Released in 1995 on Clark’s album Cold Dog Soup, the song never chased chart success and never needed to. It belongs to a tradition far older than rankings and radio play — the tradition of songs that tell the truth quietly, songs that stay with you long after the final note fades.

Placed early on Cold Dog Soup, an album widely regarded as one of Guy Clark’s most reflective and finely written works, this song immediately sets the emotional tone. The album itself did not produce major charting singles, but it earned deep respect among listeners who value songwriting as an art of restraint and honesty. By the mid-1990s, Clark was already recognized as one of America’s great storytellers — a songwriter’s songwriter — and this track stands as one of his most devastatingly subtle achievements.

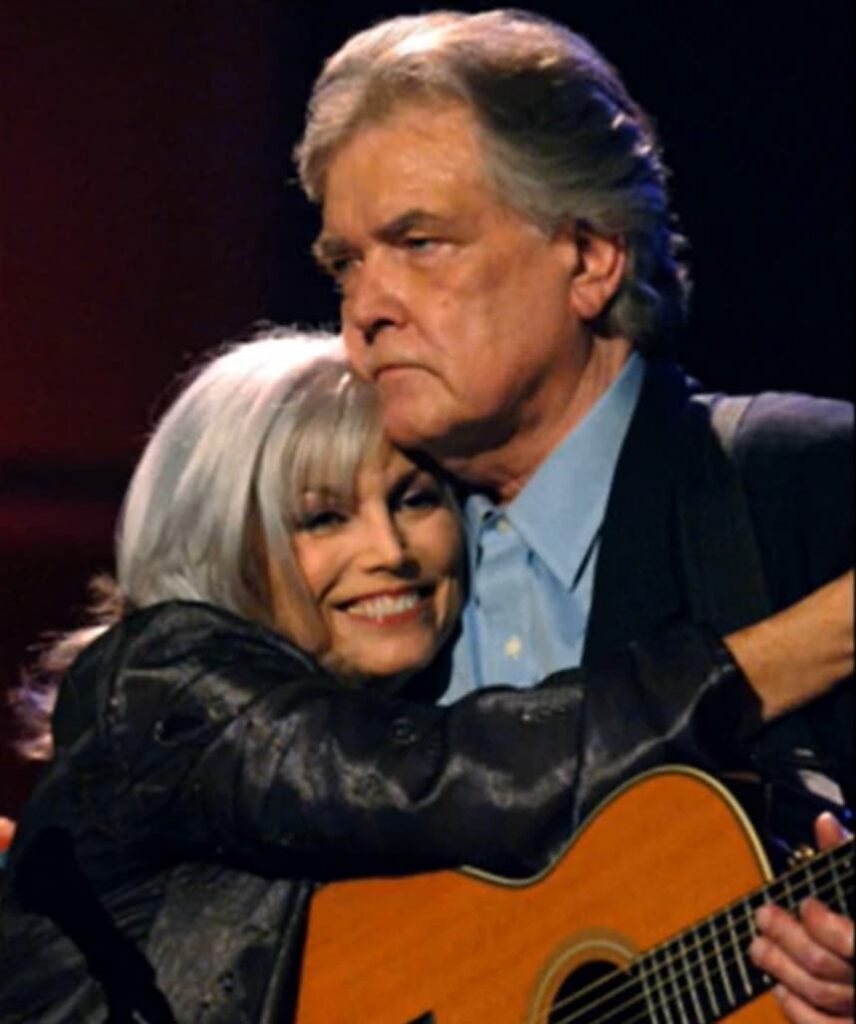

The pairing with Emmylou Harris is crucial. Her voice does not overpower or dramatize; instead, it hovers like a memory, gentle and unresolved. Where Clark’s delivery feels grounded and weary, Harris brings an almost ghost-like tenderness. Together, they sound less like two singers performing and more like two people standing in the quiet aftermath of something once precious.

At its core, “I Don’t Love You Much, Do I” is not about the absence of love — it is about love that still exists, painfully so, but no longer has a place to live. The title itself is pure Guy Clark: plainspoken, conversational, and quietly brutal. It sounds like something said not in anger, but in resignation — a line spoken aloud to convince oneself of something the heart does not fully believe.

There are no grand metaphors here, no sweeping declarations. Instead, the song unfolds through small emotional gestures: distance, hesitation, things left unsaid. The narrator seems to circle around the truth, testing it gently, as if afraid that speaking it too clearly might shatter what remains. And that is where the song finds its power. Love, Clark suggests, does not always end with a dramatic farewell. Sometimes it simply thins out, leaving behind a hollow space where closeness used to be.

The duet format deepens this sense of emotional tension. When Harris joins Clark, she does not contradict him, nor does she plead. Her presence feels like memory answering memory — two voices acknowledging the same loss from opposite sides of the same silence. It is a masterclass in emotional economy, proving how little needs to be said when the truth is fully felt.

For listeners who have lived long enough to understand that love can fade without disappearing entirely, this song lands with particular weight. It speaks to the quiet endings — the ones that arrive without slammed doors or raised voices, the ones that unfold slowly, over time, until one day you realize something essential has changed. That realization, Clark captures, is often the hardest part.

Cold Dog Soup marked a period when Guy Clark was writing with remarkable clarity and restraint, and this song embodies that maturity. There is no bitterness here, no blame. Only acceptance, and the sadness that comes with it. In a world that often celebrates love’s beginning, “I Don’t Love You Much, Do I” dares to linger on its gentle unraveling.

Years later, the song remains a quiet companion for those reflective moments when memory surfaces uninvited. It does not demand attention; it waits patiently. And when you return to it, it feels unchanged — honest, fragile, and profoundly human.