The Legend on the Rails: Ramblin’ Jack Elliott’s Take on an American Folk Outlaw

Oh, to be young again, sitting cross-legged on a dusty floor, the scratch and hiss of the needle on a vinyl record filling the air. For many of us who came of age during the folk revival, the voice of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott was the authentic sound of the road, the open heart of the rambling man, carrying forward the songs of his mentor, Woody Guthrie. And among those essential tracks, none captured the spirit of outlaw defiance and frontier legend quite like “Railroad Bill.”

This is not a song with a traditional “chart position” in the way pop hits of the day were measured. “Railroad Bill” is a folk standard, a traditional ballad, and Elliott’s definitive recording of it appeared on his 1962 album, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott (Prestige/International). The album itself was reissued in 1989 as part of a double LP called Hard Travelin’, but the song’s true measure lies not in Billboard numbers, but in its persistent presence in the canon of American folk music, where it served as a foundational piece for generations of guitar players and singers. It was one of those early pieces that taught fingerpicking rudiments to many an aspiring folk artist, making it a chart-topper in the world of the guitar-toting troubadour.

The meaning of “Railroad Bill” is rooted in the rich, complex history of the American South. The song is a ballad about the real-life figure Morris Slater, an African American man in the 1890s who became an outlaw after a confrontation with a deputy sheriff over a repeating rifle in Florida. He soon found himself at odds with the Louisville and Nashville (L&N) Railroad, earning the moniker “Railroad Bill” because he frequented the train lines. His modus operandi was to jump boxcars, throwing out stolen merchandise—often provisions and goods—for others to collect.

The story behind it became the stuff of legend. In the eyes of poor sharecroppers and turpentine workers along the L&N tracks, many of them Black, Railroad Bill was a modern-day Robin Hood. He took from the powerful and gave to the needy, making him a folk hero in a time when many felt exploited and powerless. The sheer audacity of his escapes—including a legend that he could transform himself into an animal, like a cat or a dog, to elude the authorities—only solidified his mythical status. His shooting of Escambia County Sheriff Edward S. McMillan in 1895 escalated the hunt, yet Bill continued to evade capture for a time, leading to verses being added to the rapidly growing folk song every time he pulled a new prank or escape. The fact that the authorities, upon his eventual death in 1896, paraded his body across the region to prove he was indeed mortal only served to reinforce the belief among his admirers that his spirit, the spirit of defiance, lived on.

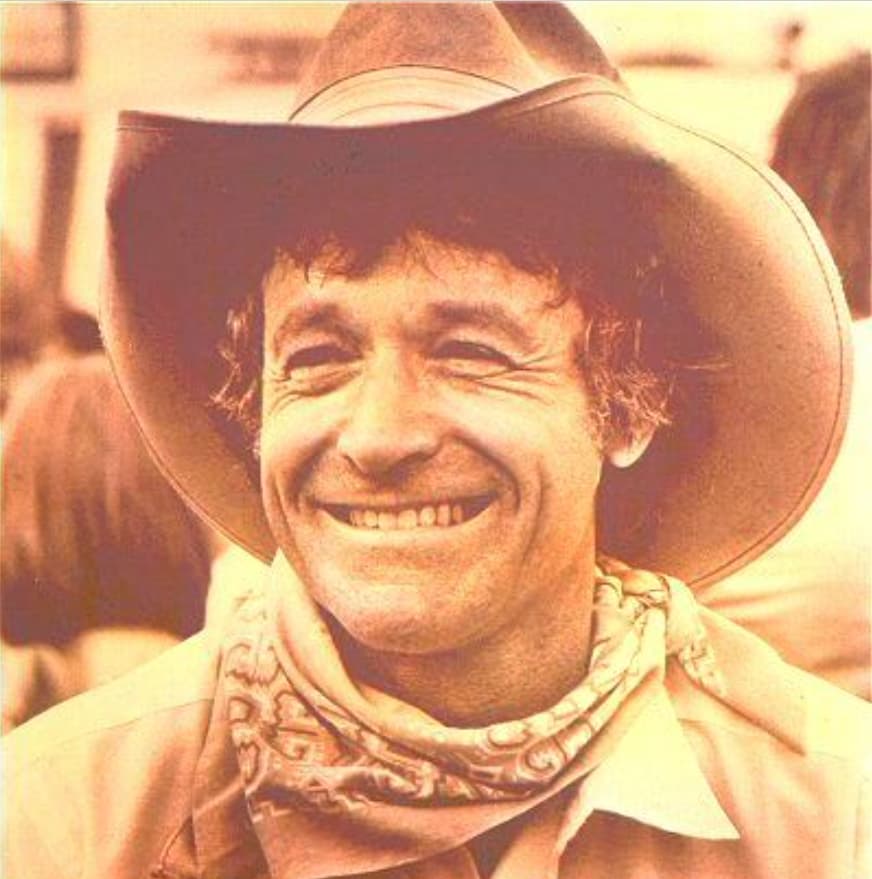

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott’s interpretation—like his entire musical persona—is suffused with a genuine, lived-in feel, bringing a sophisticated guitar style and world-weary voice to the simple, repeating stanzas of the traditional song. His version, which he recorded in 1961/1962, carries the echoes of countless previous iterations, from the earliest field recordings to his own mentor’s influence. Elliott was famous for “rambling,” not just in his travels but in his long, winding stories and conversational style, a trait that gave his performances an intimacy and authenticity that the younger folk generation, including Bob Dylan, would later seek to emulate. Listening to his guitar work on “Railroad Bill,” you can almost feel the rhythmic clack of the train on the track, the dust of the Alabama turpentine camps, and the twinkle in the eye of a trickster who outran the law, if only in song. It’s a bittersweet sound, a relic of an older, harder America, but one where even the outlaw could become a legend.