You Got to Die — a stark gospel-blues reminder that time, truth, and judgment spare no one

When Blind Willie McTell recorded “You Got to Die” in the early 1930s, he was not aiming for fame, radio play, or commercial glory. He was doing something far more enduring: delivering a solemn message drawn from scripture, street wisdom, and lived experience. The song, recorded in 1933 during a session for Vocalion Records, never appeared on any music chart — at that time, blues and gospel recordings by Black artists were rarely tracked in such a way. Yet its absence from rankings only underscores its deeper power. This is not a song meant to climb upward. It looks straight ahead, and finally downward, into the unavoidable truth of mortality.

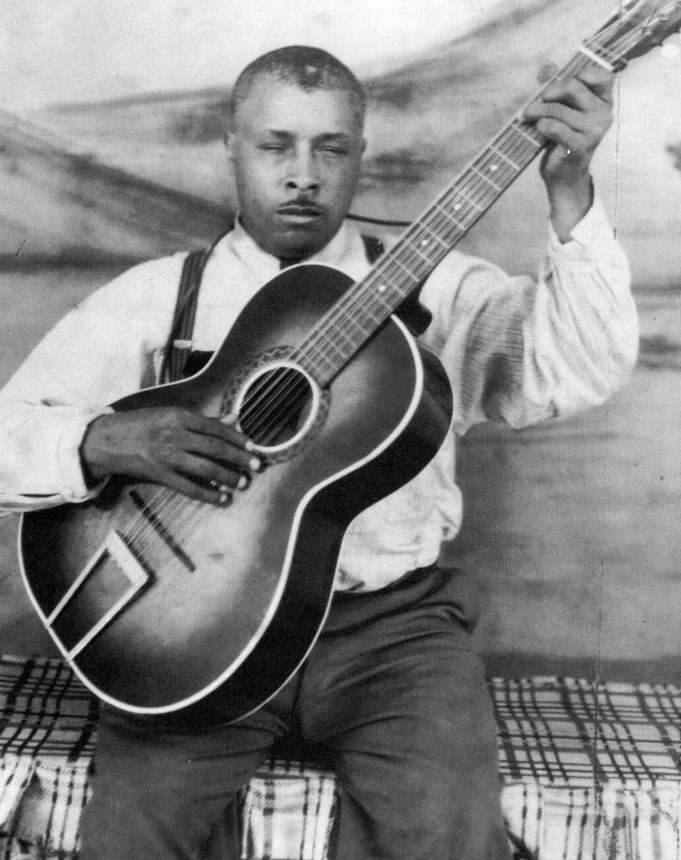

By the time Blind Willie McTell recorded “You Got to Die,” he was already a seasoned musician. Born in 1898 and blind from birth, McTell had absorbed the musical traditions of the American South with remarkable depth. He was fluent in blues, ragtime, gospel, and folk, and he possessed a rare technical mastery of the twelve-string guitar. Unlike many blues singers who leaned heavily on bravado or raw emotional display, McTell sang with restraint — calm, clear, and almost conversational. That restraint is precisely what makes “You Got to Die” so unsettling.

The song unfolds like a sermon delivered without raised voice or dramatic flourish. McTell does not threaten; he reminds. Over a steady, unadorned guitar line, he sings of judgment day, of the soul’s reckoning, of the moment when wealth, status, and earthly pride lose all meaning. The message is simple and uncompromising: no matter who you are or what you have done, you will face the end. And when that moment comes, excuses will not matter.

What sets “You Got to Die” apart from many gospel-blues recordings of its era is its tone. There is no attempt to comfort the listener with promises of easy redemption. Nor is there despair. Instead, there is clarity. McTell sounds like a man who has thought long and carefully about life’s limits and has come to accept them. His delivery suggests not fear, but understanding — as if he is passing along knowledge learned the hard way.

The historical context matters. In the early 1930s, America was deep in the Great Depression. Poverty, illness, and early death were not abstractions; they were daily realities. For many listeners at the time, McTell’s words would have felt painfully close to home. Yet the song does not dwell on suffering. It shifts the focus inward, asking the listener to consider how they live, not how long they live.

For modern ears, especially those shaped by decades of popular music that often avoids the subject of death or disguises it with sentimentality, “You Got to Die” can feel bracing. There is no metaphor here elaborate enough to soften the blow. Death is named plainly. Judgment is unavoidable. And still, the song does not feel cruel. It feels honest.

This honesty is central to Blind Willie McTell’s legacy. He was not a performer chasing trends; he was a chronicler of truths that outlasted fashion. While his name would later be immortalized by Bob Dylan in “Blind Willie McTell,” it is songs like “You Got to Die” that reveal why his influence runs so deep. McTell understood that music could carry wisdom as well as beauty — that a song could serve as a mirror.

For listeners who have traveled far in life, who have seen certainty fade and priorities shift, this song resonates in a quiet, profound way. It does not scold. It does not rush. It simply stands there, steady as time itself, reminding us that every road ends, and that meaning is found not in avoiding that truth, but in facing it with clear eyes.

In the end, “You Got to Die” is not about fear of death. It is about respect for life — and for the choices that define it. Long after the final chord fades, its message lingers, calm and unyielding, like a voice speaking from across generations, asking us to listen while we still can.