“For Lovin’ Me” — A wistful farewell wrapped in folk chords

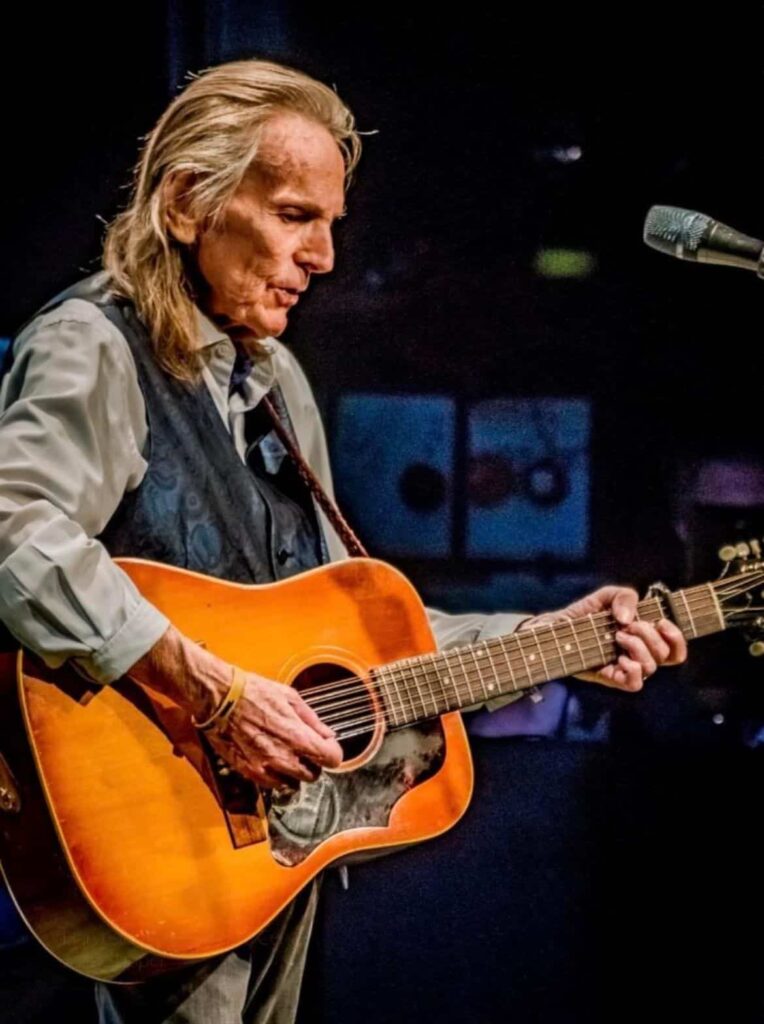

Artist: Gordon Lightfoot

Release year (his version): 1965 on Lightfoot!

Chart position (as covered by Peter, Paul & Mary): #30 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100.

Songwriter: Gordon Lightfoot.

When I sit back and let the gentle finger-picked guitar of “For Lovin’ Me” drift in, I feel transported to a late hazy afternoon — sunlight filtering through lace curtains, a half-empty teacup beside you, and a page of memories gently turning in the silence. This is a song that opens quietly, but leaves a long, lingering sigh.

The story behind the tune

Gordon Lightfoot, the Canadian troubadour whose name would later rise to great heights, composed the song in the early 1960s. At the time, he was still finding his voice, still carving out space in the folk world beyond Canada. The first widespread exposure for this composition came not from him, but from Peter, Paul & Mary, who released their version in December 1964 (single) and had it reach #30 in the U.S. pop chart by early 1965. That success opened doors — Lightfoot himself later admitted that “For Lovin’ Me” marked his first reach into a broader audience.

Though Lightfoot recorded his own version on his debut album (1966’s Lightfoot!) and it circulated then, the chart-making moment remains with the PPM version. According to sources, Lightfoot himself later wryly described the song as “likely the most chauvinistic song ever written.”

What the song means

On the surface, “For Lovin’ Me” presents a confident lover’s departure: the narrator tells his partner that everything they had is gone: “That’s what you get for lovin’ me / Everything you had is gone as you can see.” It’s a brusque farewell, laced with bravado: “I’ve got a hundred more like you / So don’t be blue”.

But beneath that bravura lies something more subtle — a sense of movement, of impermanence. “Movin’ is my stock in trade / I’m movin’ on,” he sings. He isn’t just leaving a relationship; he’s leaving a place, a moment, perhaps even a part of himself. This layered meaning resonates strongly for those of us who’ve known the ache of departure, of being the one who stays behind while another walks away.

And for the listener past middle age, this song evokes that moment when time itself says we must move on — when the familiar fades, when what once mattered slips out of focus. The folk simplicity of the arrangement amplifies the emotional weight: this isn’t a stadium production, but a small room, a single guitar, and a voice swallowing memories. It lingers in the heart, un-mannered and honest.

Why it matters

“For Lovin’ Me” holds a special place in Lightfoot’s catalogue: it may not be his most celebrated later hit (that honour goes to songs like The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald or Sundown), but it was the one that first carried his songwriting beyond his Canadian roots. It planted a seed for what was to come.

Moreover, for fans of the folk era it stands as a kind of snapshot — mid-60s, acoustic guitars, voices harmonising, the folk revival in full gentle flight. It bridges the youthful fervour of the early 60s and the reflective depth that singer-songwriters would bring in the 70s. It reminds us that parting ways need not always erupt in drama — sometimes it comes with a handful of chords and a resigned exhale.

Closing reflections

As you listen to “For Lovin’ Me”, perhaps close your eyes and imagine that afternoon light, the worn leather armchair, the soft hum of a record spinning. Think of years passed, of friends lost and found, of journeys taken and those yet to begin. The song doesn’t just speak of a breakup — it speaks of time slipping through our fingers, the impermanence of love, and the quiet dignity of moving onward.

And for those who lived through those decades — who watched vinyls, turned down the volume so as not to disturb the moment, who felt life change its shape — this song offers a companionable nod. It acknowledges that yes, the world changes. The lovers change. We change. But the guitar still plays, the voice still sings, and the memory lingers.

In the hush after the final chord, we are left with something quietly powerful: the knowledge that “what you get for lovin’ me” is both the absence of permanence, and the presence of a moment felt deeply — a moment never entirely lost.