Tie a Yellow Ribbon — a simple ribbon that carried hope, forgiveness, and the promise of coming home

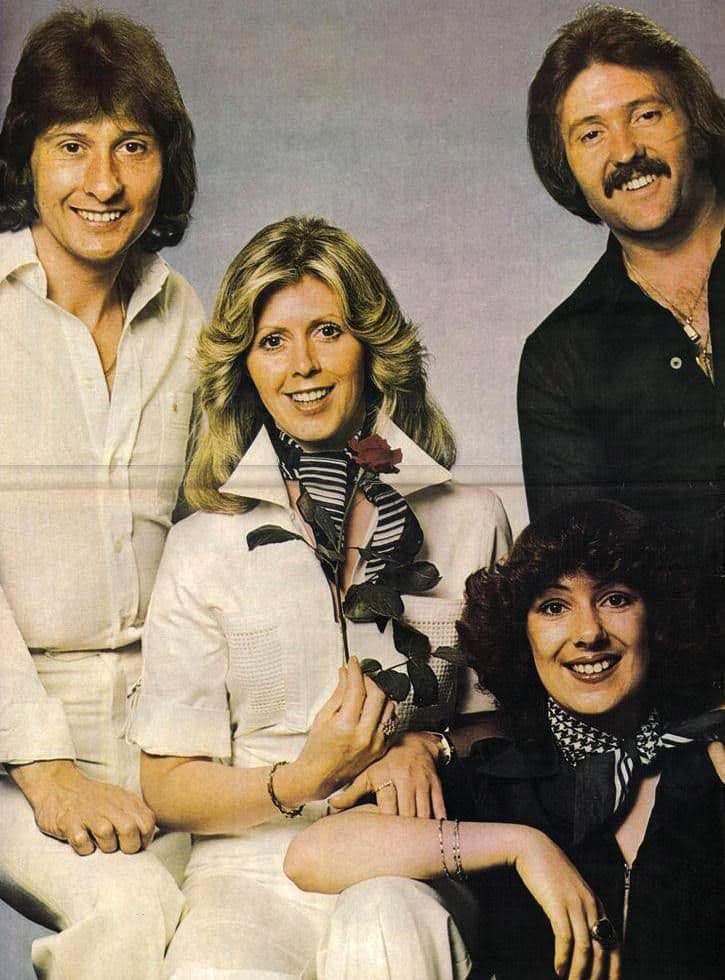

Few songs have ever captured the idea of returning — not just physically, but emotionally — as powerfully and as simply as “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree”. When Brotherhood of Man released their version in 1973, the song had already begun to live a life far larger than a single recording. Yet their interpretation gave it a distinctly gentle, reflective tone, one that resonated deeply with listeners who understood what it meant to wait, to hope, and to forgive.

Let us place the essential facts first. “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree” was written by Irwin Levine and L. Russell Brown and was first recorded and made famous in early 1973. In the United Kingdom, Brotherhood of Man’s version reached No. 1 on the UK Singles Chart, becoming one of the defining hits of that year. It stood alongside — and in many places rivaled — the hugely successful American version by Tony Orlando and Dawn, which topped the Billboard Hot 100 in the United States. But for British listeners, it was Brotherhood of Man who carried this story into their homes and hearts.

The song’s narrative is deceptively simple. A man is returning home after a long absence — strongly implied to be prison — uncertain whether he is still welcome. Instead of demanding an answer, he asks for a sign: if forgiveness is possible, let a yellow ribbon be tied around the old oak tree. If not, he will remain on the bus and quietly pass by. In just a few lines, the song opens a world of vulnerability, humility, and quiet dignity.

What gives Brotherhood of Man’s recording its lasting emotional weight is restraint. Their delivery is warm but not theatrical, hopeful but never sentimental. The harmonies feel communal, almost neighborly, as if the song is being told not by a single voice, but by a village that understands the pain of separation and the power of second chances. When the chorus arrives, it does not shout triumph — it breathes relief.

By the time the bus reaches the tree and the ribbons are revealed — not just one, but “a hundred yellow ribbons” — the moment feels earned. It is not about spectacle. It is about grace. The abundance of ribbons symbolizes something deeply comforting: forgiveness not given reluctantly, but offered generously, without conditions.

The timing of the song’s success mattered. In the early 1970s, the world was still shaped by the aftermath of war, social division, and personal dislocation. Many families knew the feeling of waiting, wondering if someone would come back changed, broken, or at all. “Tie a Yellow Ribbon” gave voice to those unspoken anxieties, but it also offered reassurance — that love could survive mistakes, and that home could still be home.

For older listeners, the song often carries layered meanings. It recalls not only the story it tells, but the era it lived in: radios playing softly in kitchens, the rhythm of everyday life slowing just enough to listen. The yellow ribbon itself has since become a symbol far beyond the song — associated with waiting, remembrance, and welcome — but its emotional roots trace back to this quiet, three-minute story.

Brotherhood of Man, often remembered for their polished harmonies and accessible pop sound, reached something deeper here. This was not merely a catchy tune; it was a moral tale, a reassurance wrapped in melody. It spoke to the belief that people can change, that love can endure absence, and that forgiveness does not always need words — sometimes a ribbon on a tree is enough.

Decades later, “Tie a Yellow Ribbon” still moves listeners because it asks a question many hearts have asked in silence: Am I still wanted? And in answering with a forest of yellow ribbons, it offers one of the most tender responses popular music has ever given.