A Frosty Duet, A Timeless Tangle: Navigating the Nuances of Consent in a Bygone Era.

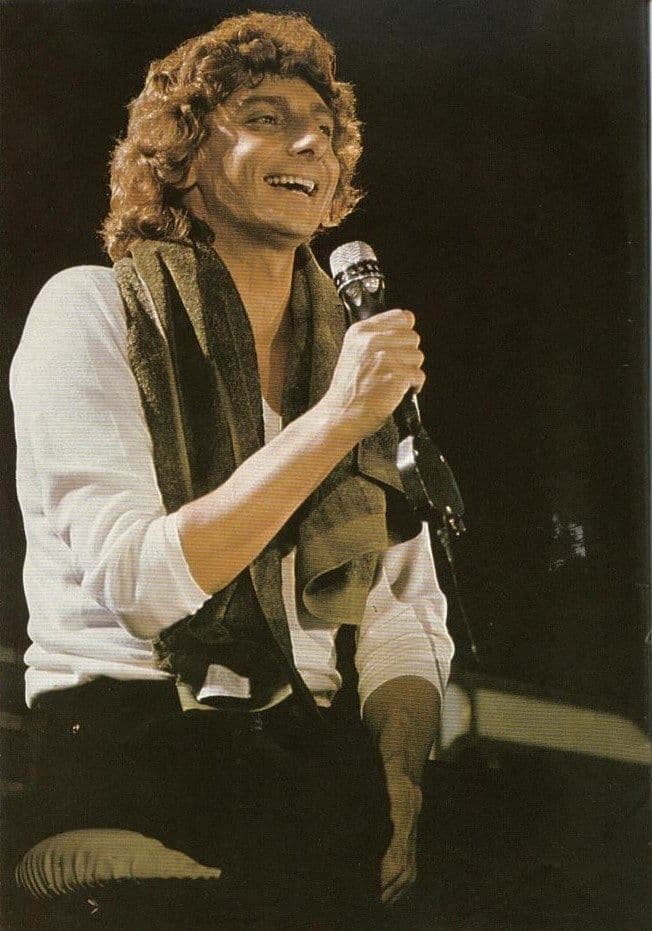

Barry Manilow and K.T. Oslin‘s rendition of “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” in 1991 revisited a classic, offering a mature, almost wistful take on a song that has, over the decades, sparked both festive cheer and heated debate. At the time of its release, while not a chart-topping single in the traditional sense, it garnered considerable airplay during the holiday season, nestled comfortably within the broader context of Manilow’s seasonal album, “Because It’s Christmas.” This particular version, however, stands out not merely for its performers, but for the subtle, almost melancholic layer it adds to the song’s already complex narrative.

The story of “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” stretches back to 1944, penned by Frank Loesser for him and his wife, Lynn Garland, to perform at parties. It was a playful, flirtatious exchange, reflecting the social mores of its time. The original intent was lighthearted, a theatrical performance of a woman trying to politely extricate herself from a gentleman’s advances, while he playfully persisted. Loesser sold the song to MGM, and it gained widespread popularity after its inclusion in the 1949 film “Neptune’s Daughter,” where it won the Academy Award for Best Original Song.

However, as societal perspectives evolved, the song’s lyrics, once seen as charmingly suggestive, began to be viewed through a more critical lens. The back-and-forth dialogue, where the woman repeatedly voices her desire to leave, while the man continues to offer reasons for her to stay, started to raise questions about consent and power dynamics. This evolution in interpretation is precisely what makes Manilow and Oslin’s rendition so compelling. It’s a performance that acknowledges the song’s history, while subtly infusing it with a sense of reflective maturity.

Oslin, known for her poignant and often bittersweet country storytelling, brings a level of world-weariness to the female role. Her voice is imbued with a sense of knowing, of having lived through the complexities of relationships and societal expectations. Manilow, ever the consummate showman, plays his part with a smooth, almost gentle persistence, never crossing the line into overt aggression. It’s a nuanced performance, one that acknowledges the song’s inherent ambiguity without necessarily resolving it.

The meaning, then, is not a simple one. It’s a reflection of the shifting sands of social discourse, a testament to how art can be reinterpreted and re-evaluated in different contexts. For older listeners, it might evoke memories of a time when social interactions were governed by a different set of rules, when playful banter and subtle flirtation were the norm. It’s a reminder of how much has changed, and how the language of love and consent has evolved.

In this duet, the chill outside becomes a metaphor for the societal pressures that once constrained women, while the warmth inside represents the allure of a moment of intimacy. Manilow and Oslin don’t simply recreate a classic; they reimagine it, adding layers of depth and complexity that invite listeners to reconsider their own perspectives on a song that has become a cultural touchstone. It’s a performance that resonates with a sense of nostalgia, not just for the song itself, but for a time when the world, for better or worse, seemed to operate on a different set of unspoken agreements. This version exists as a time capsule, a snapshot of a moment in cultural understanding, and a reminder that even the most lighthearted of songs can carry a weight of history and interpretation.